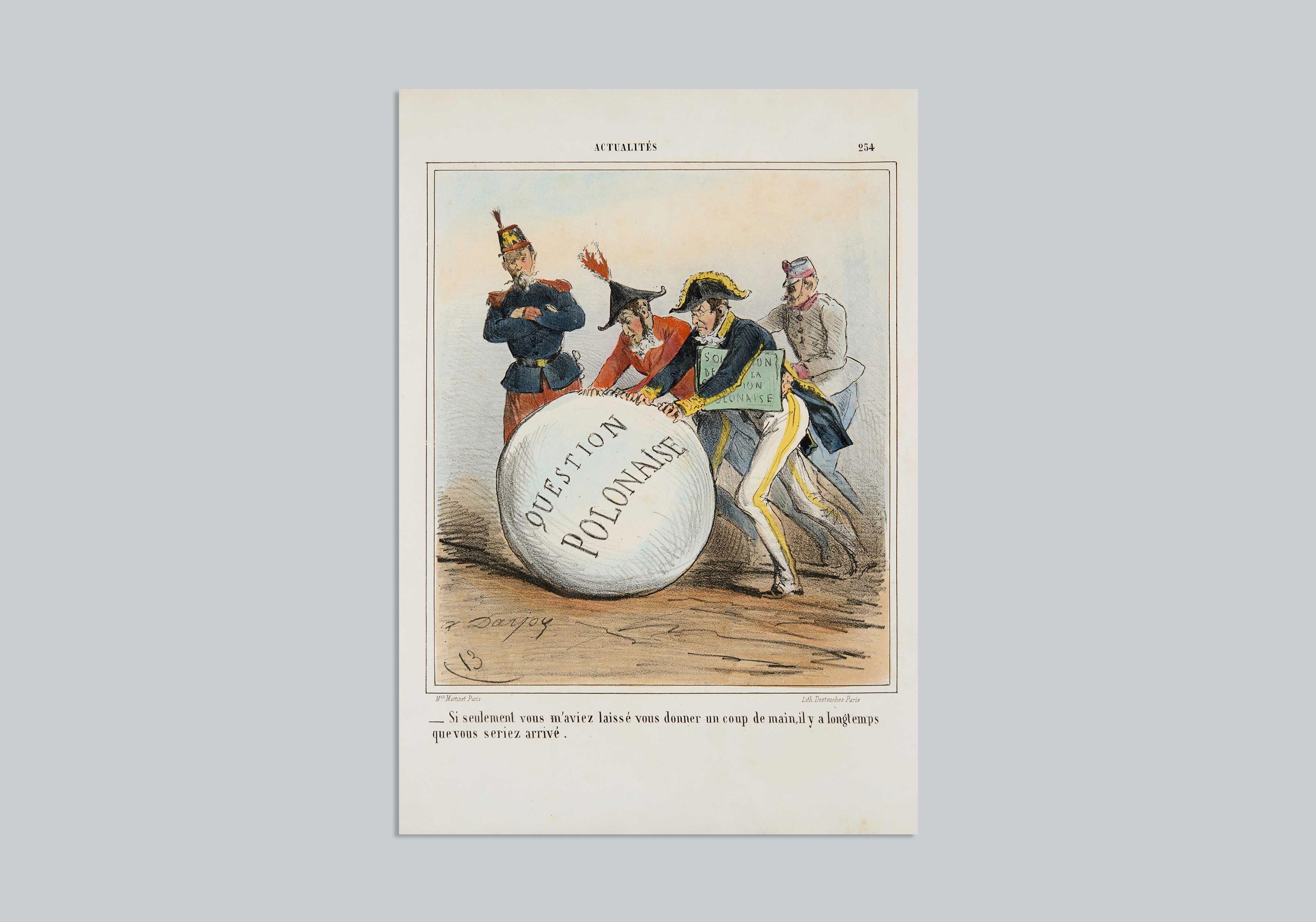

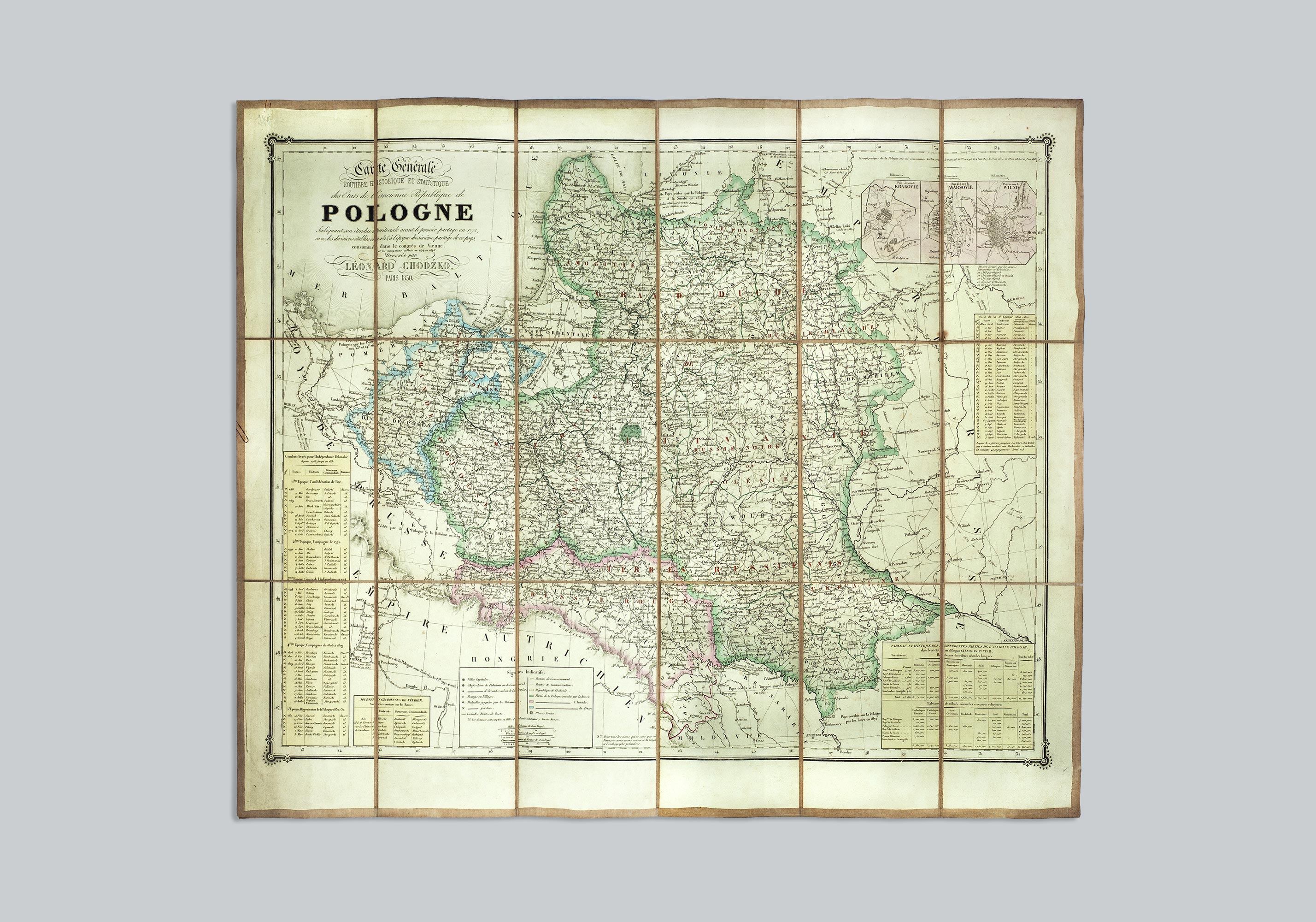

WHAT ABOUT POLAND?

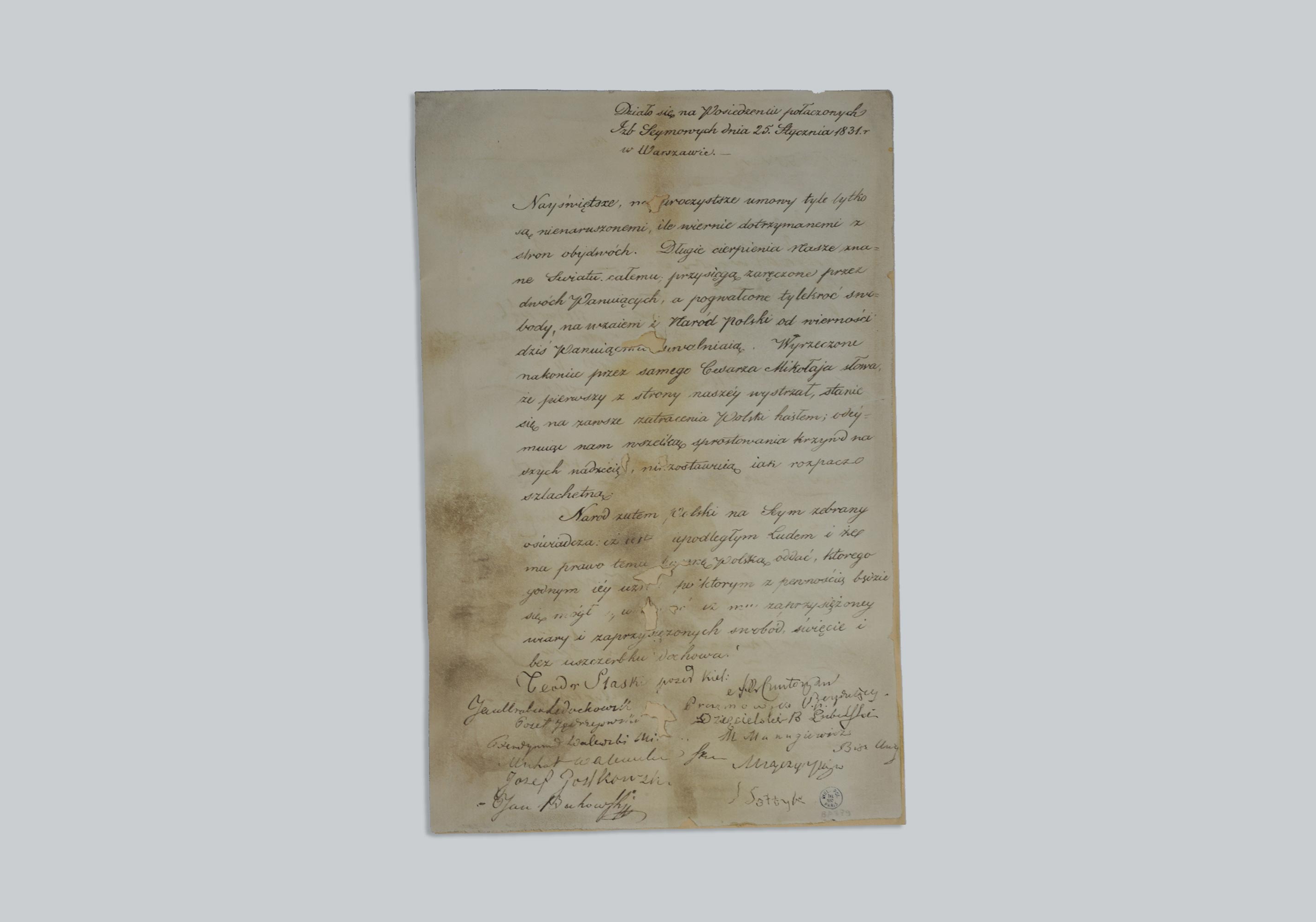

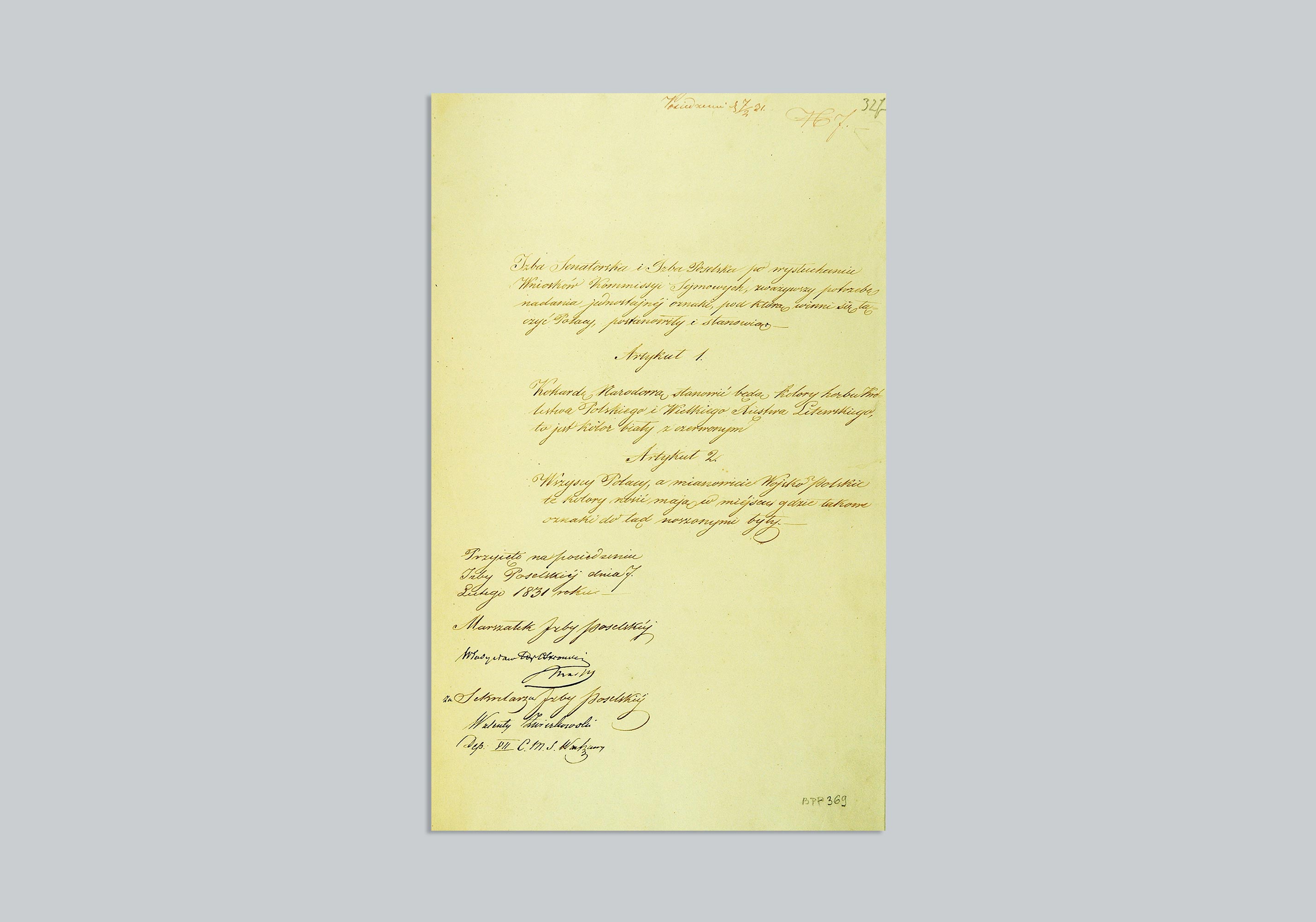

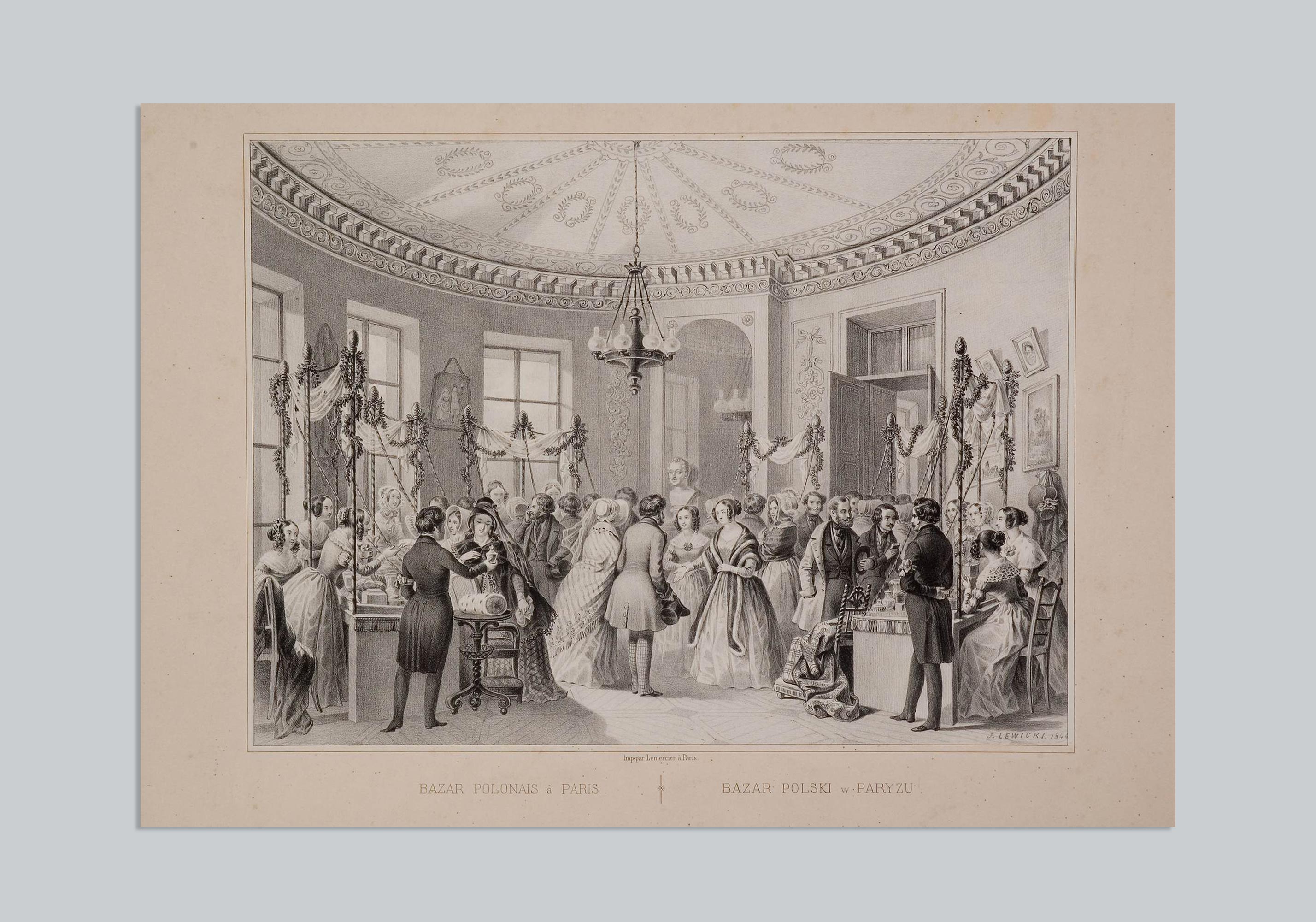

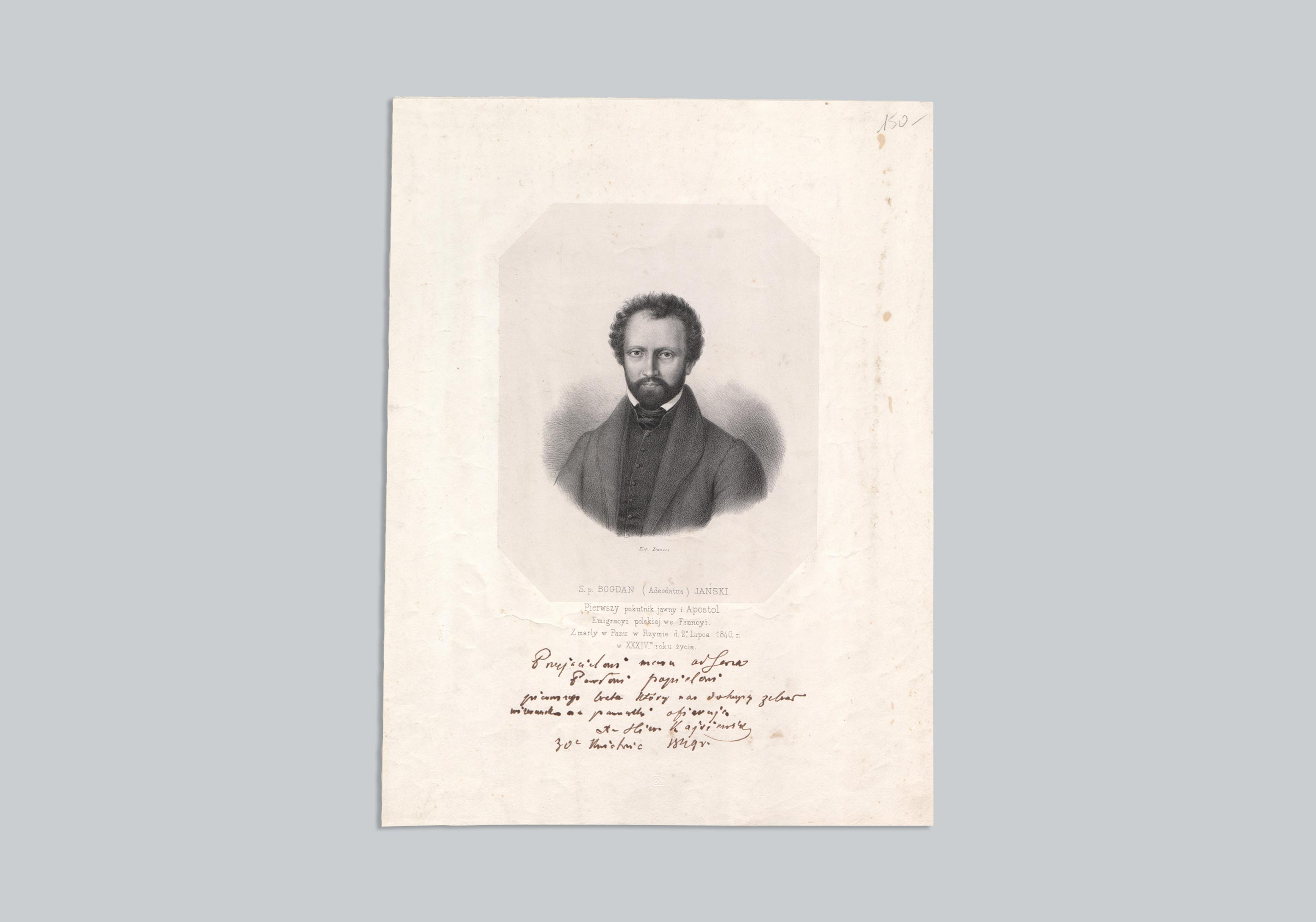

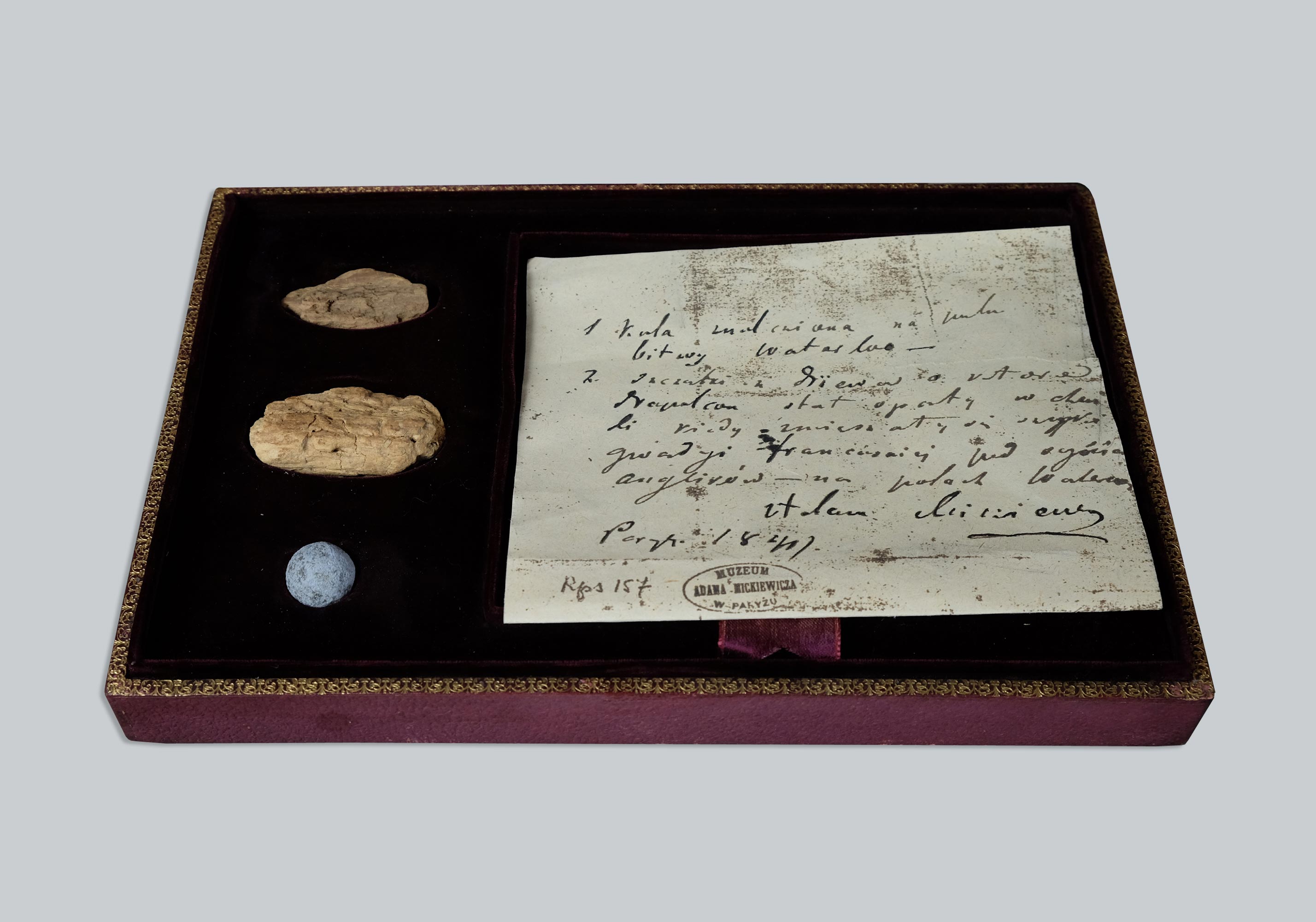

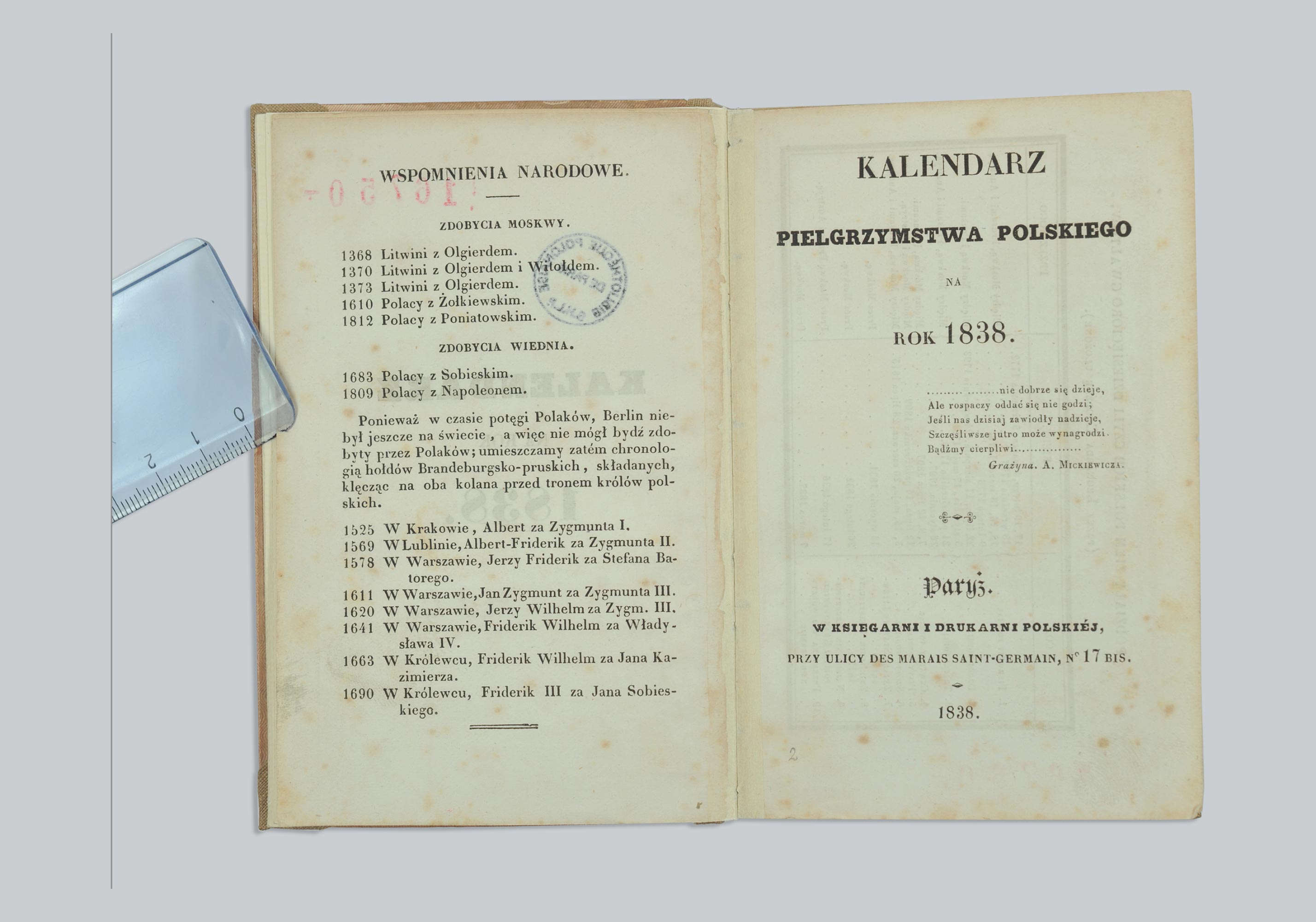

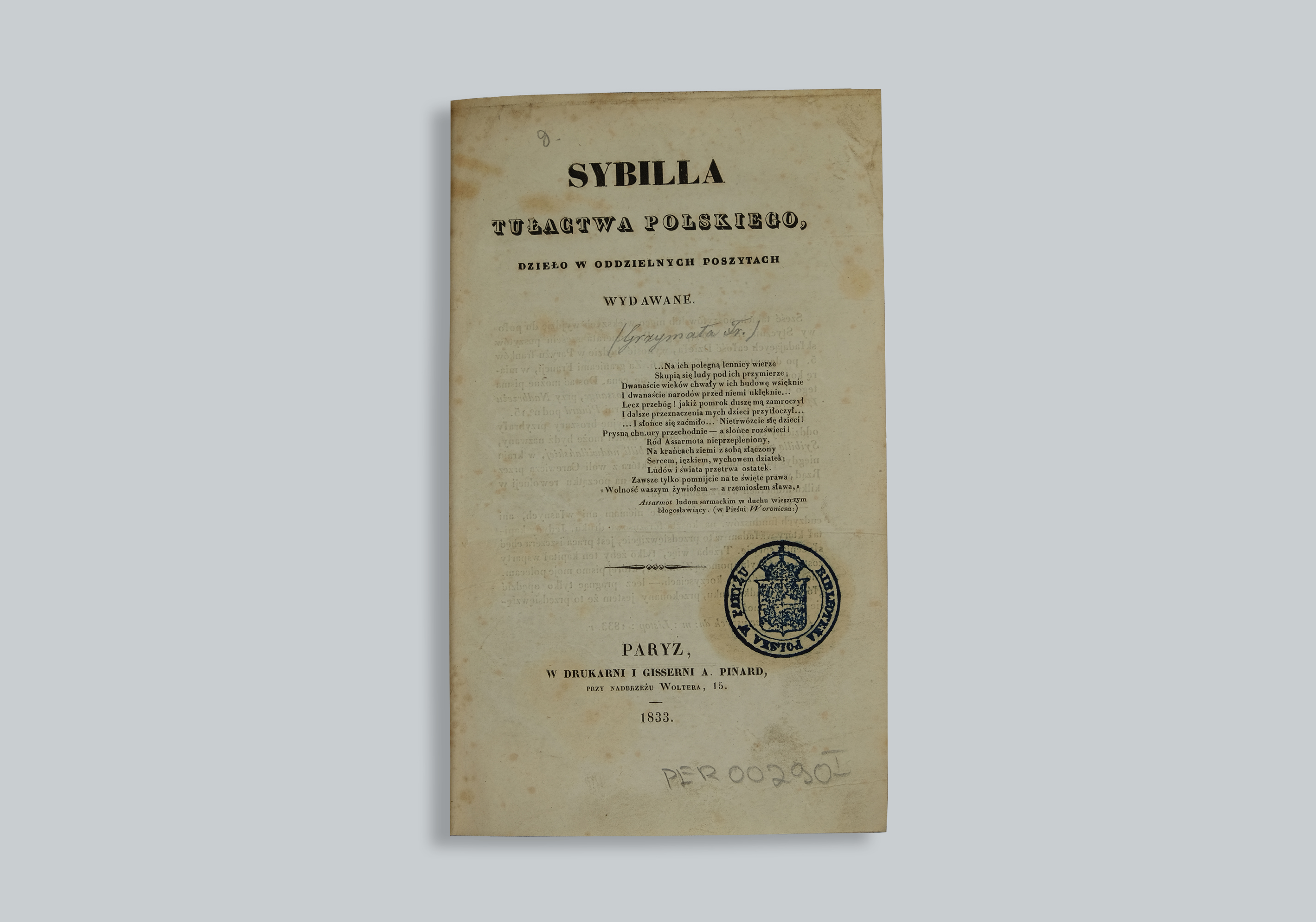

The November Uprising in 1830 was a generational experience for the first wave of Polish Romantics. The armed revolt against the Russian occupant was the most significant event of the entire 19th century for contemporary Poles.

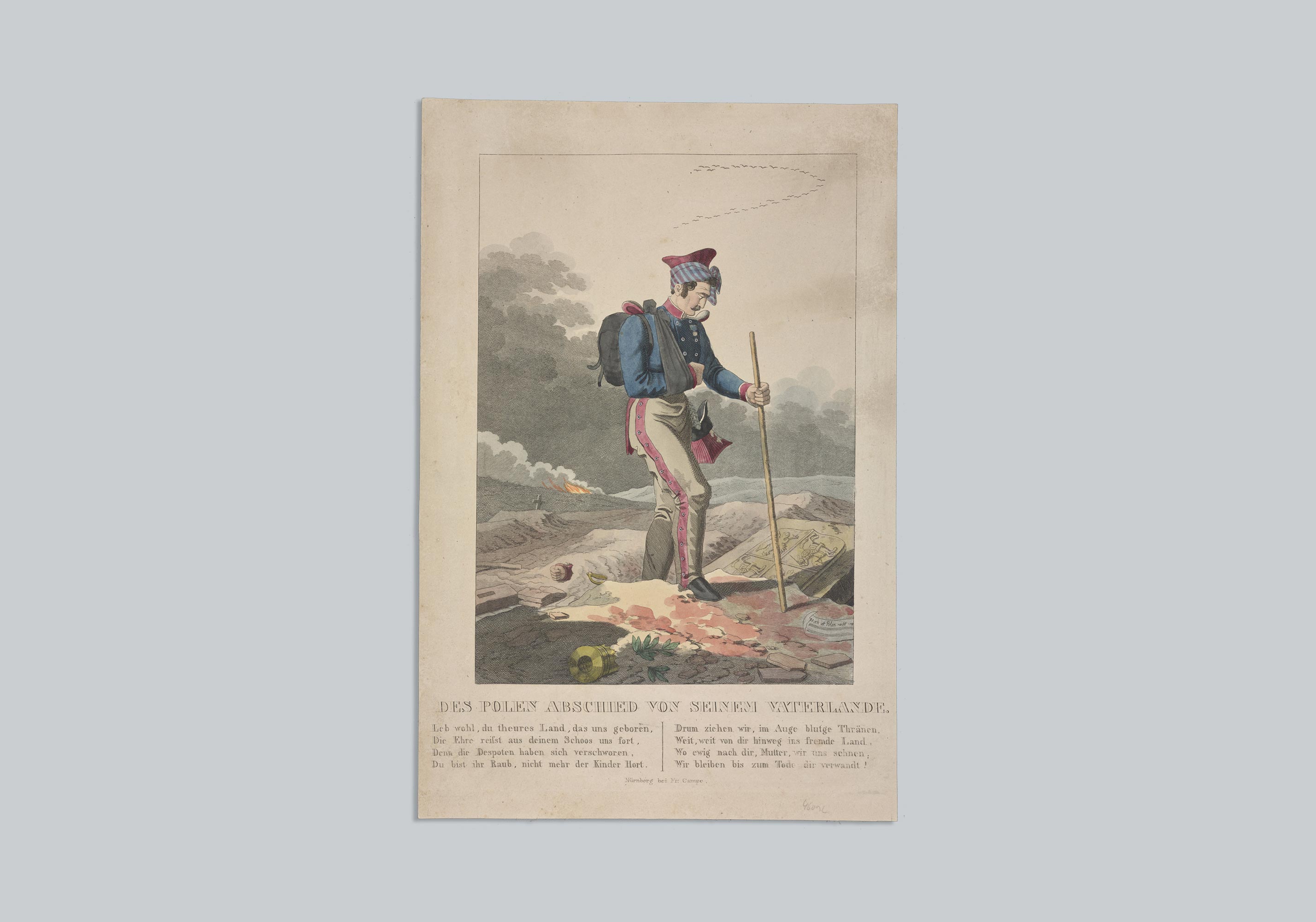

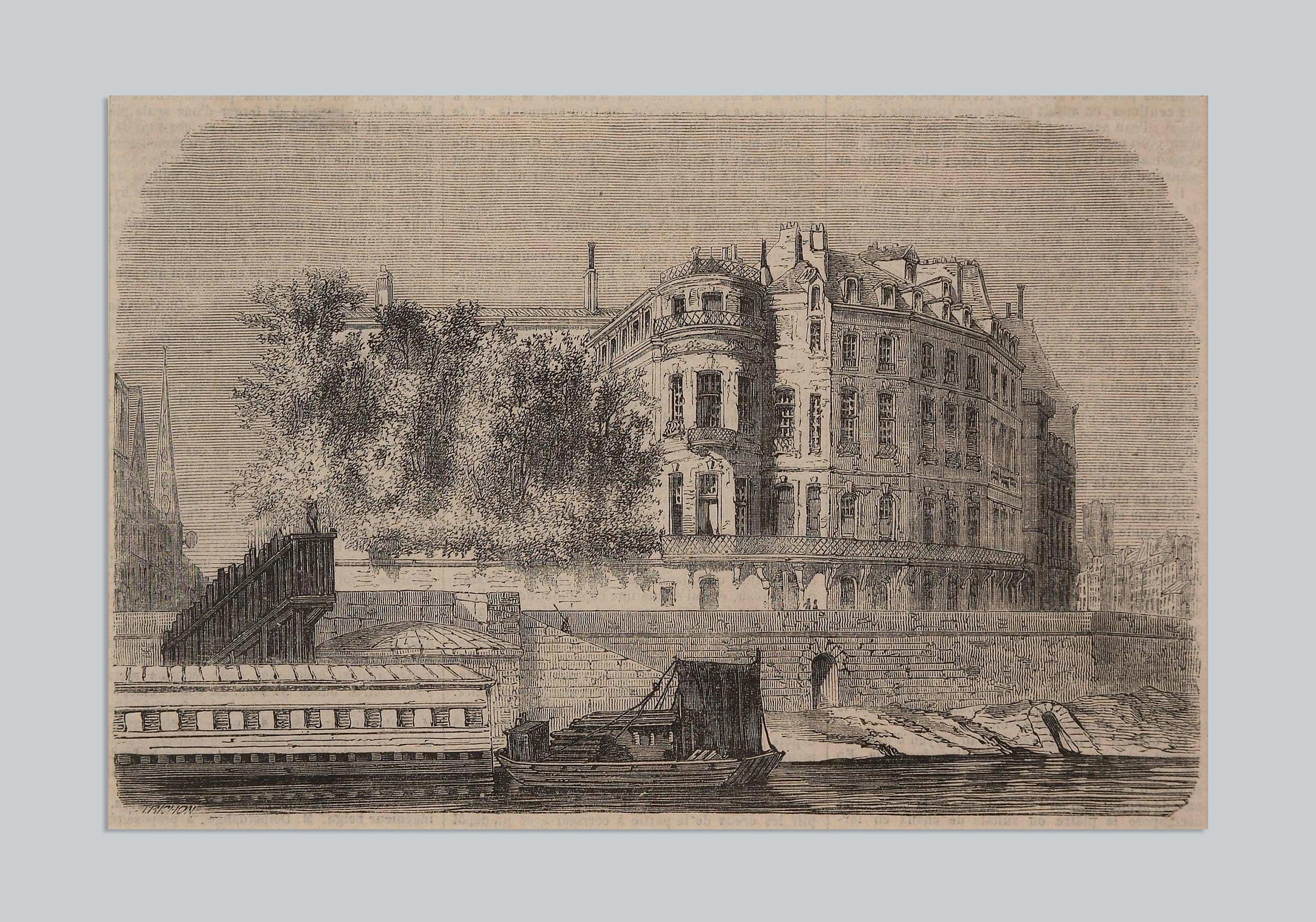

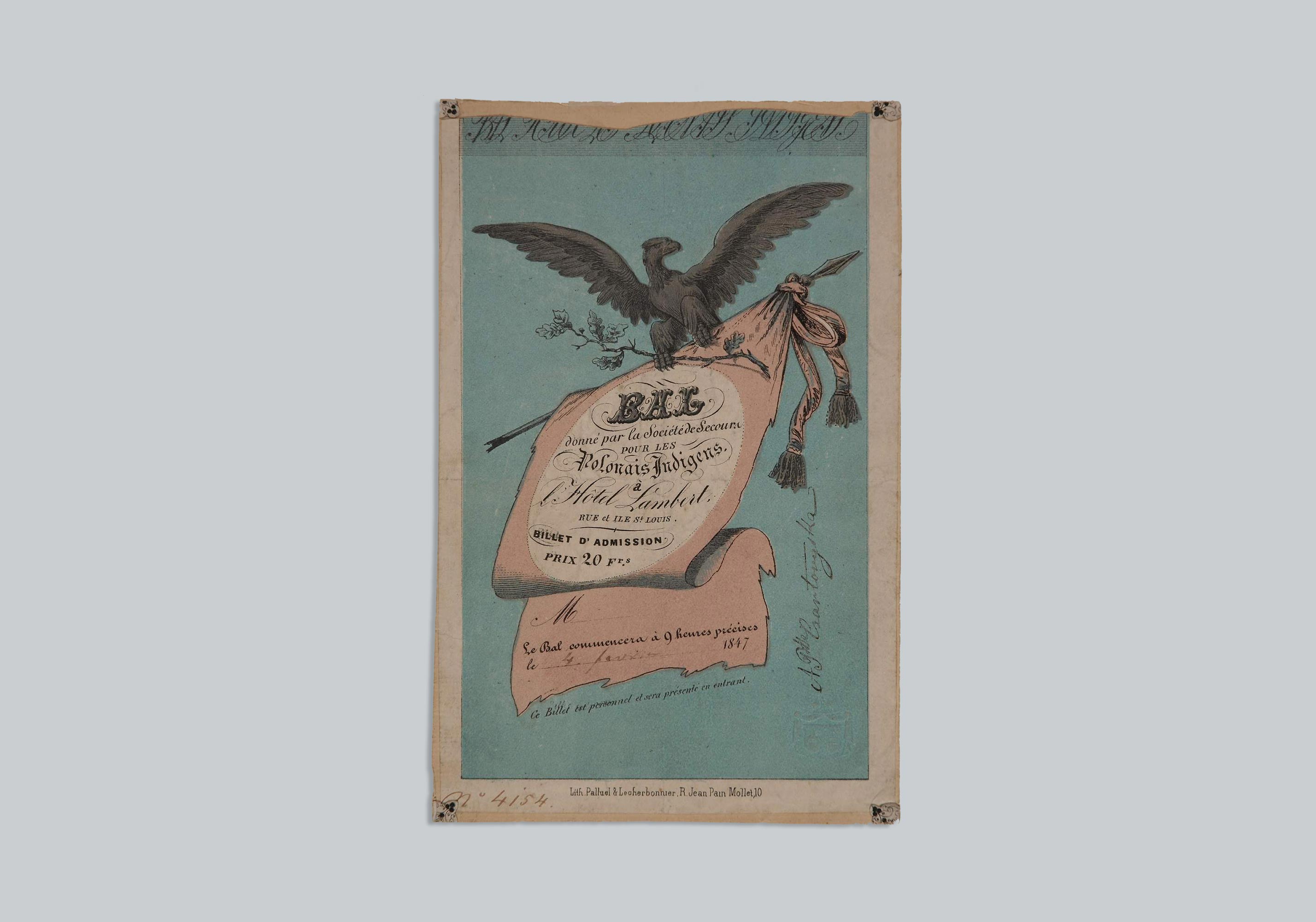

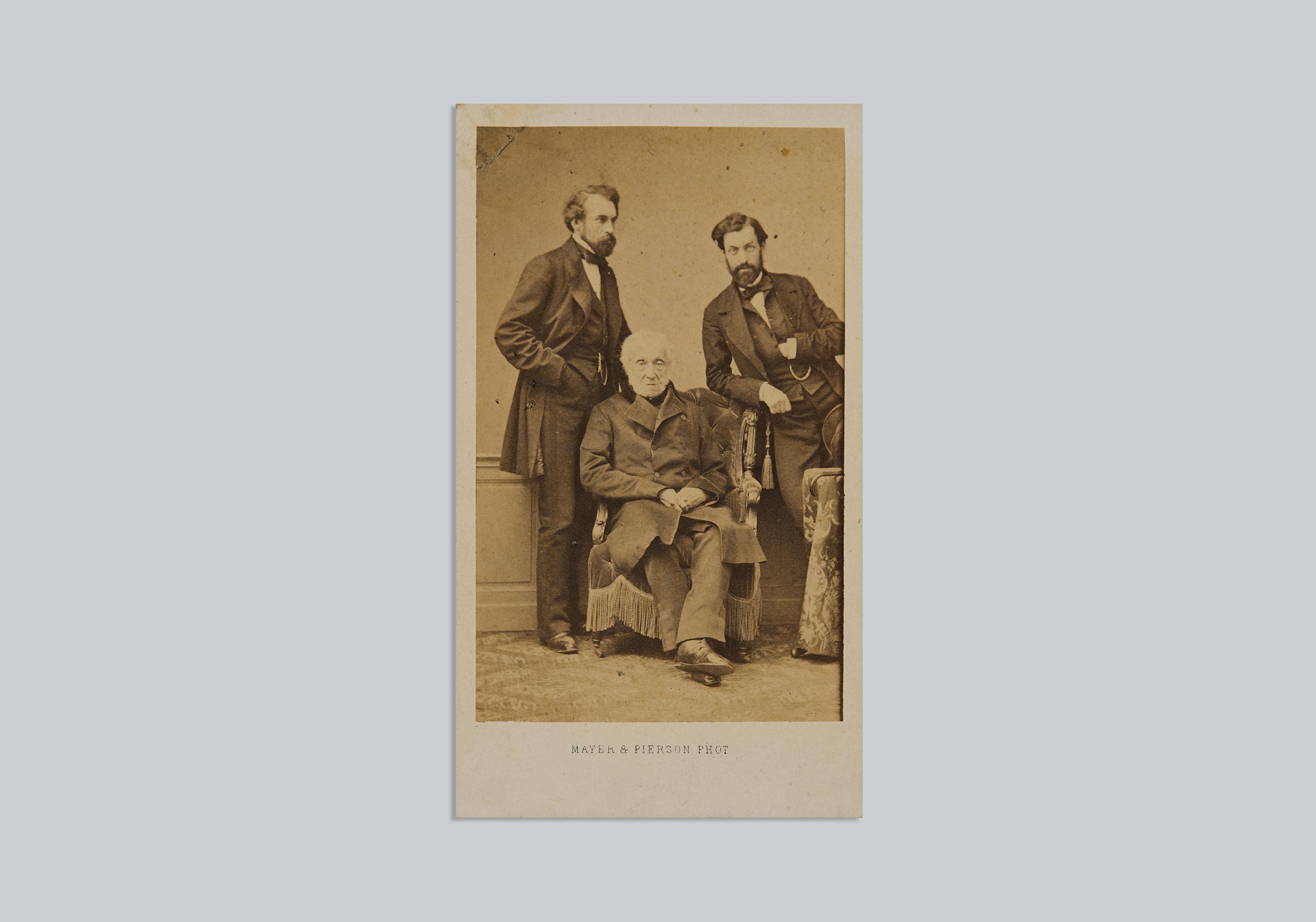

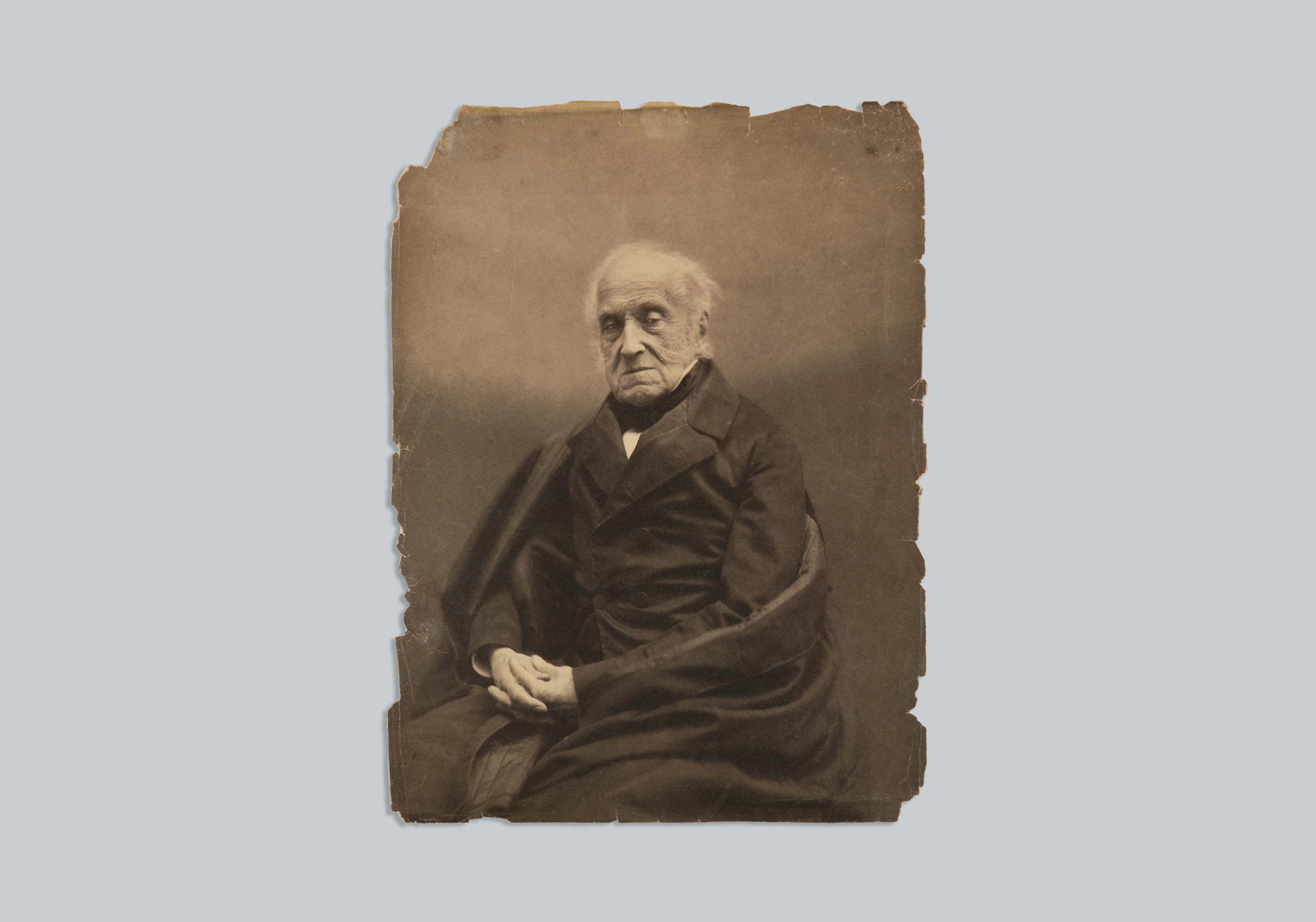

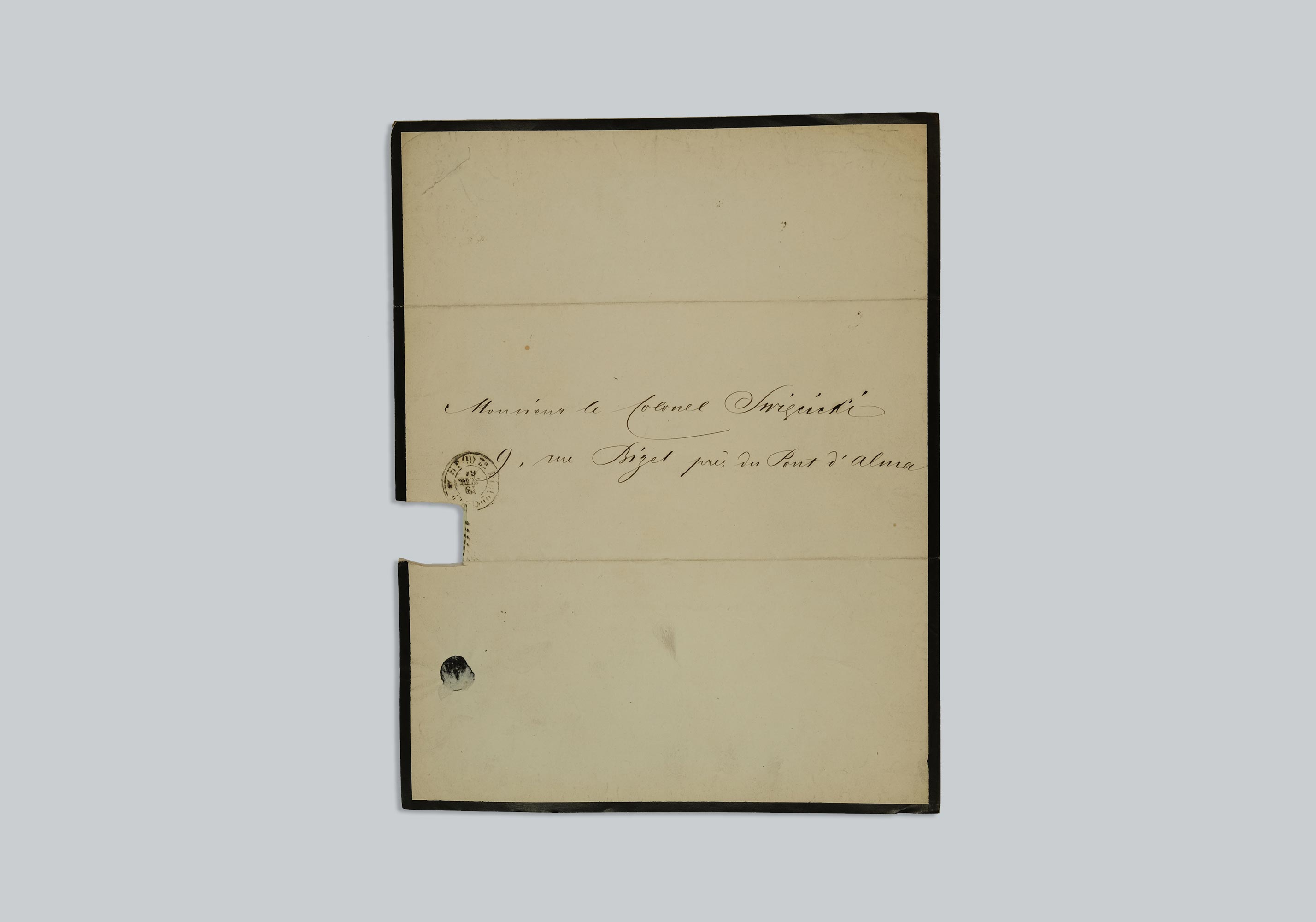

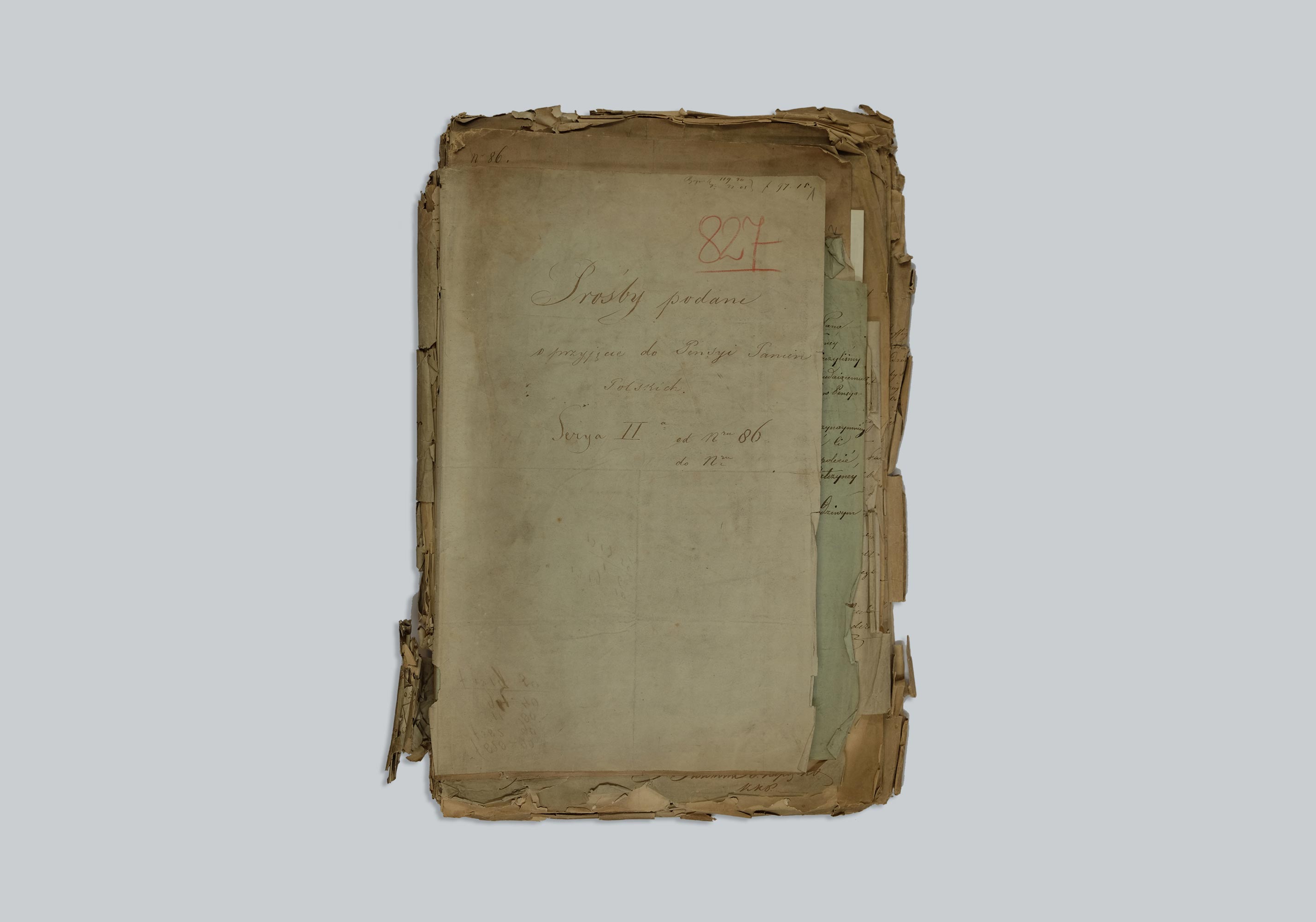

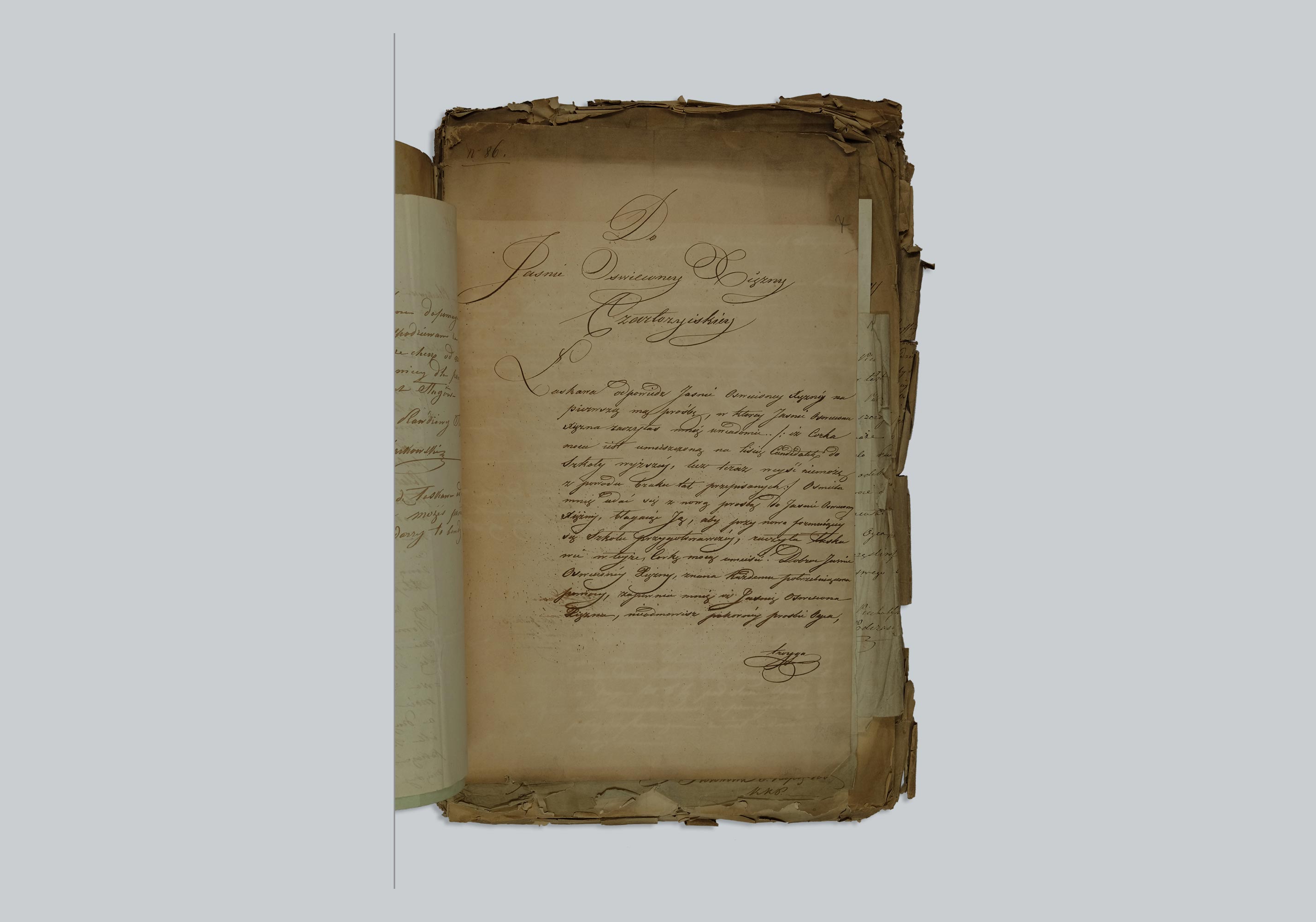

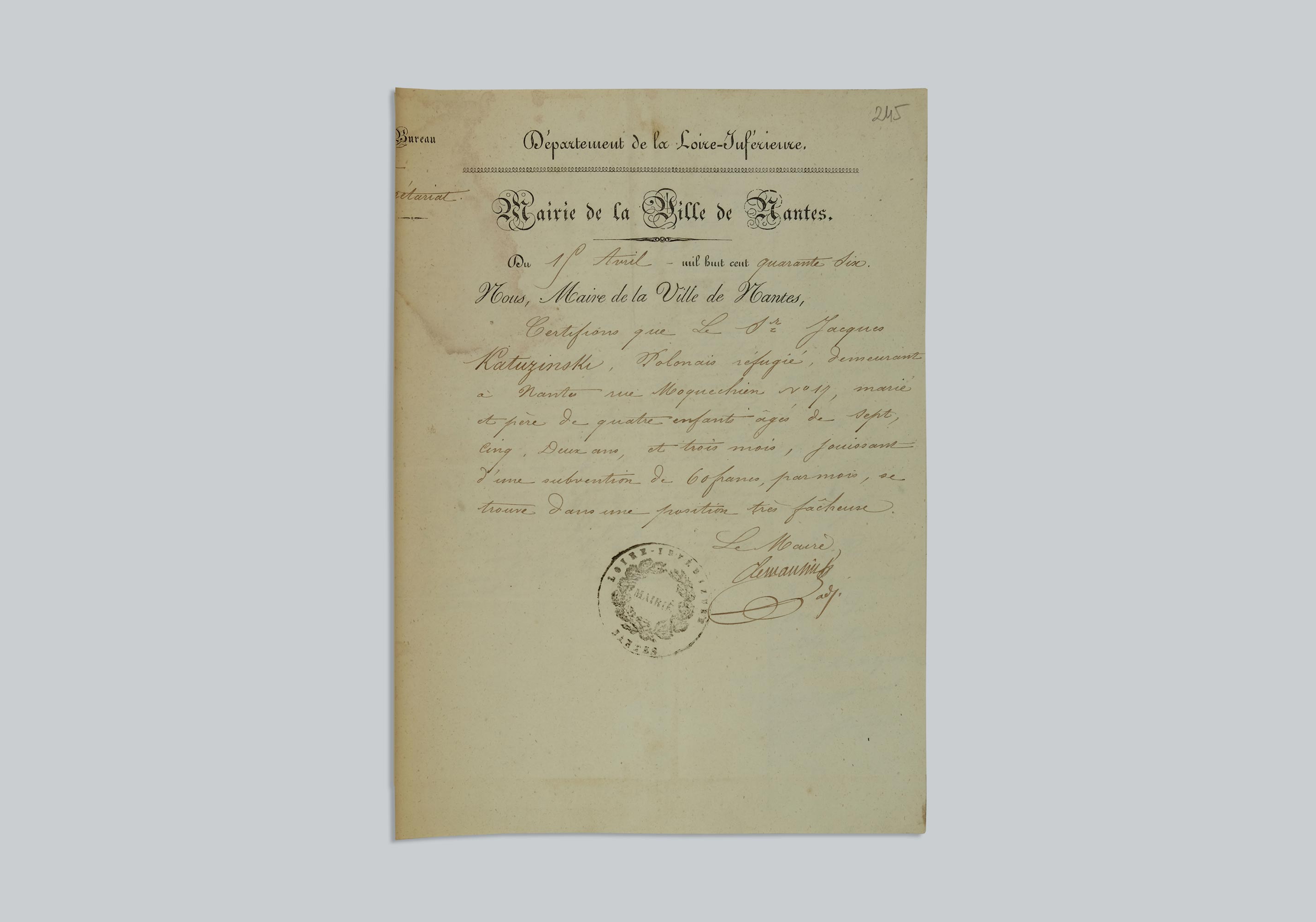

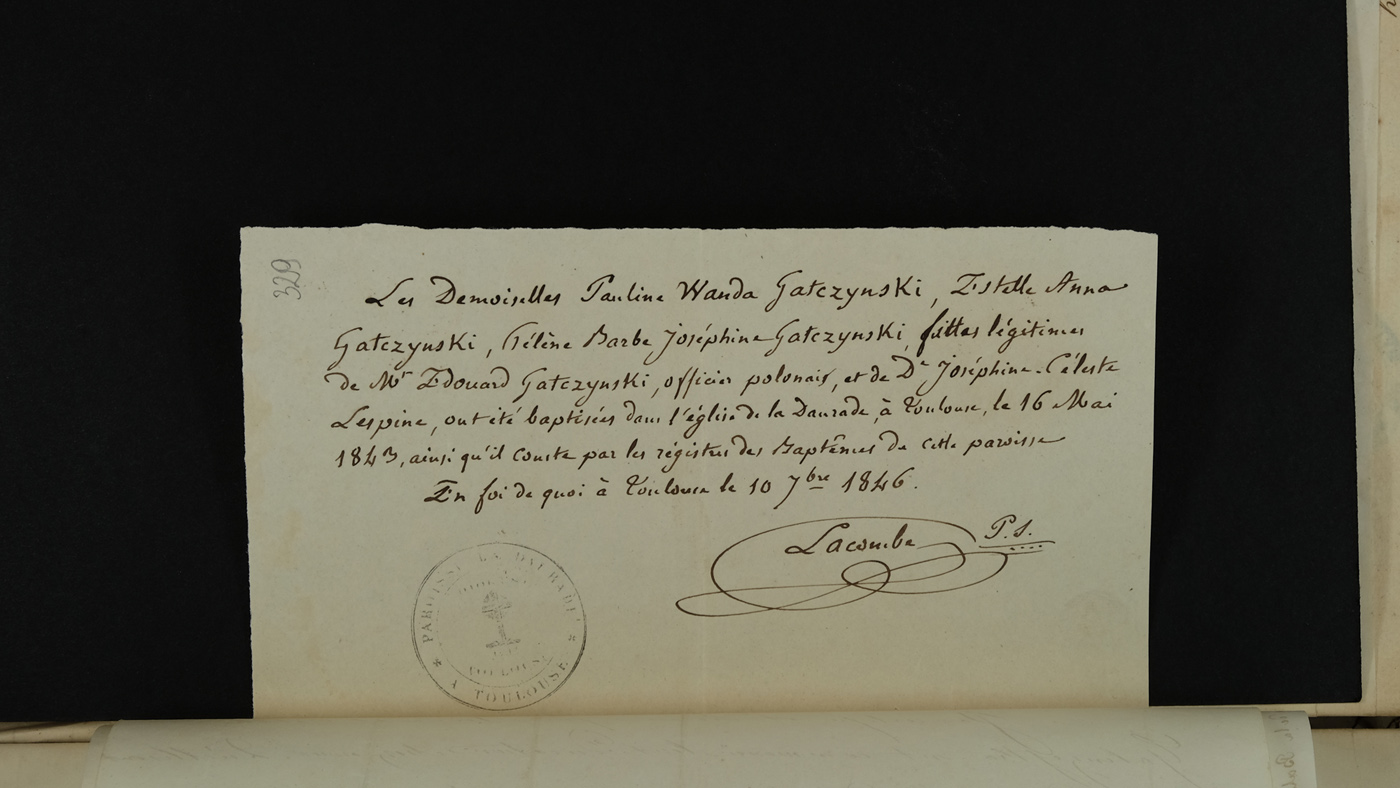

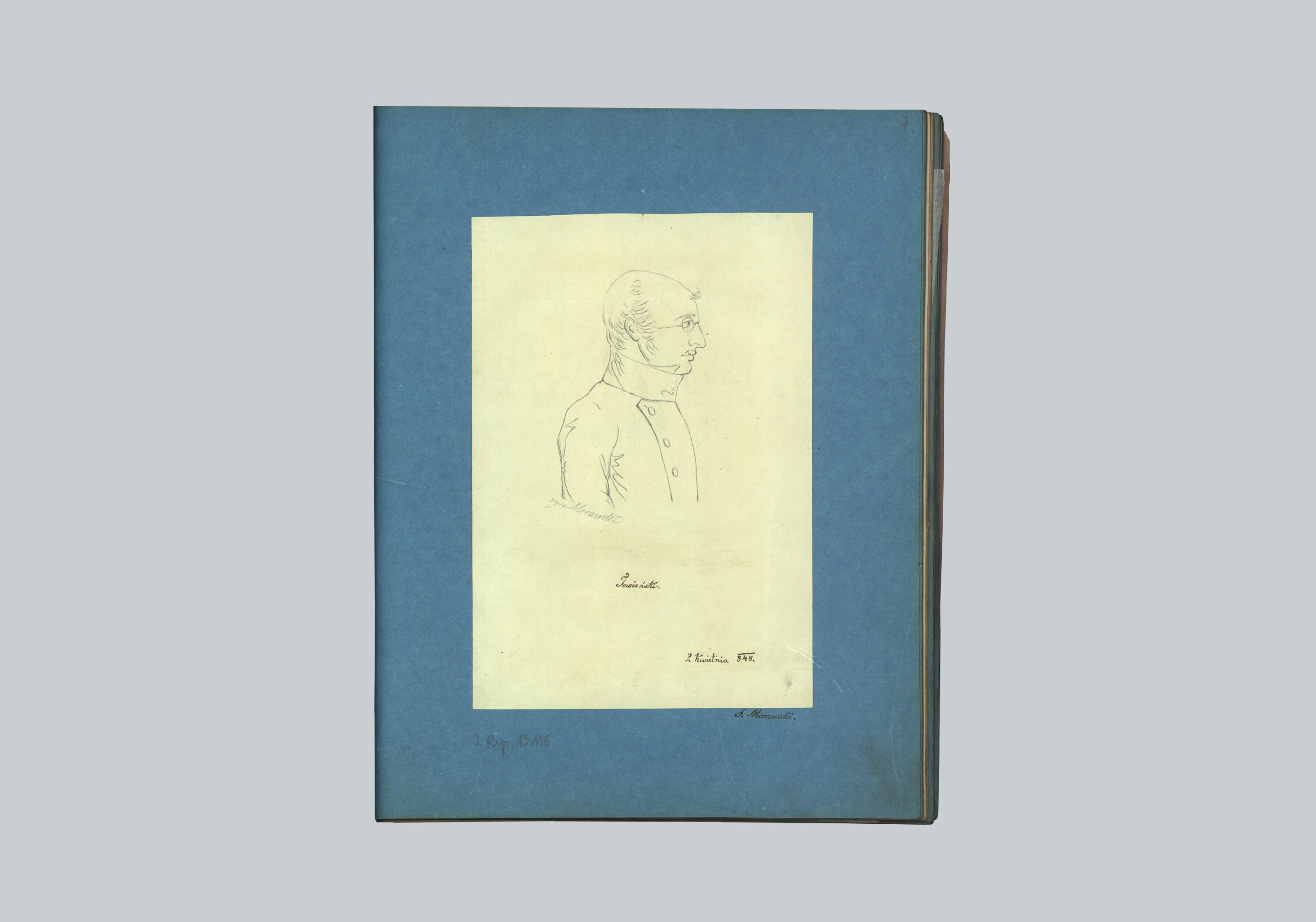

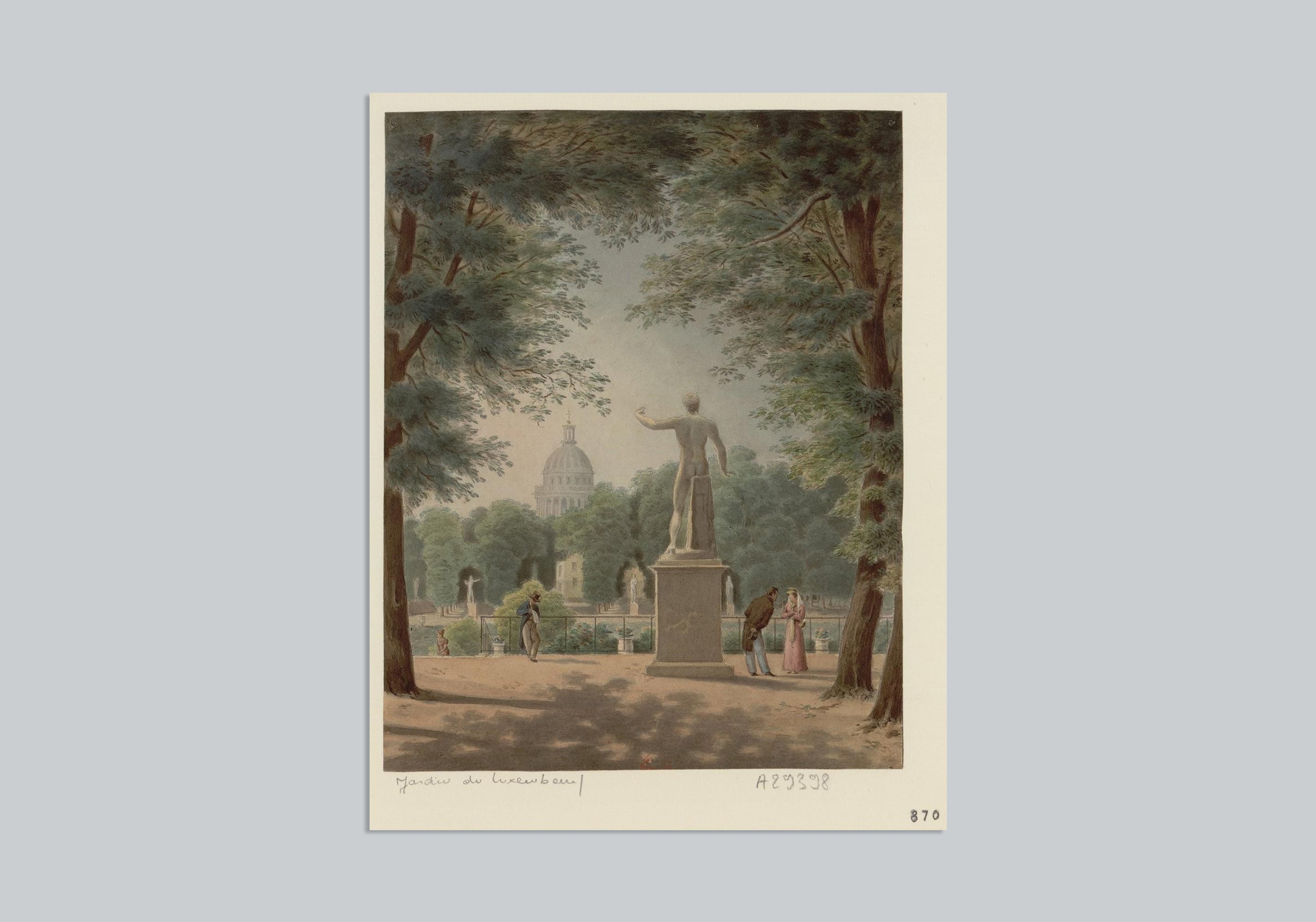

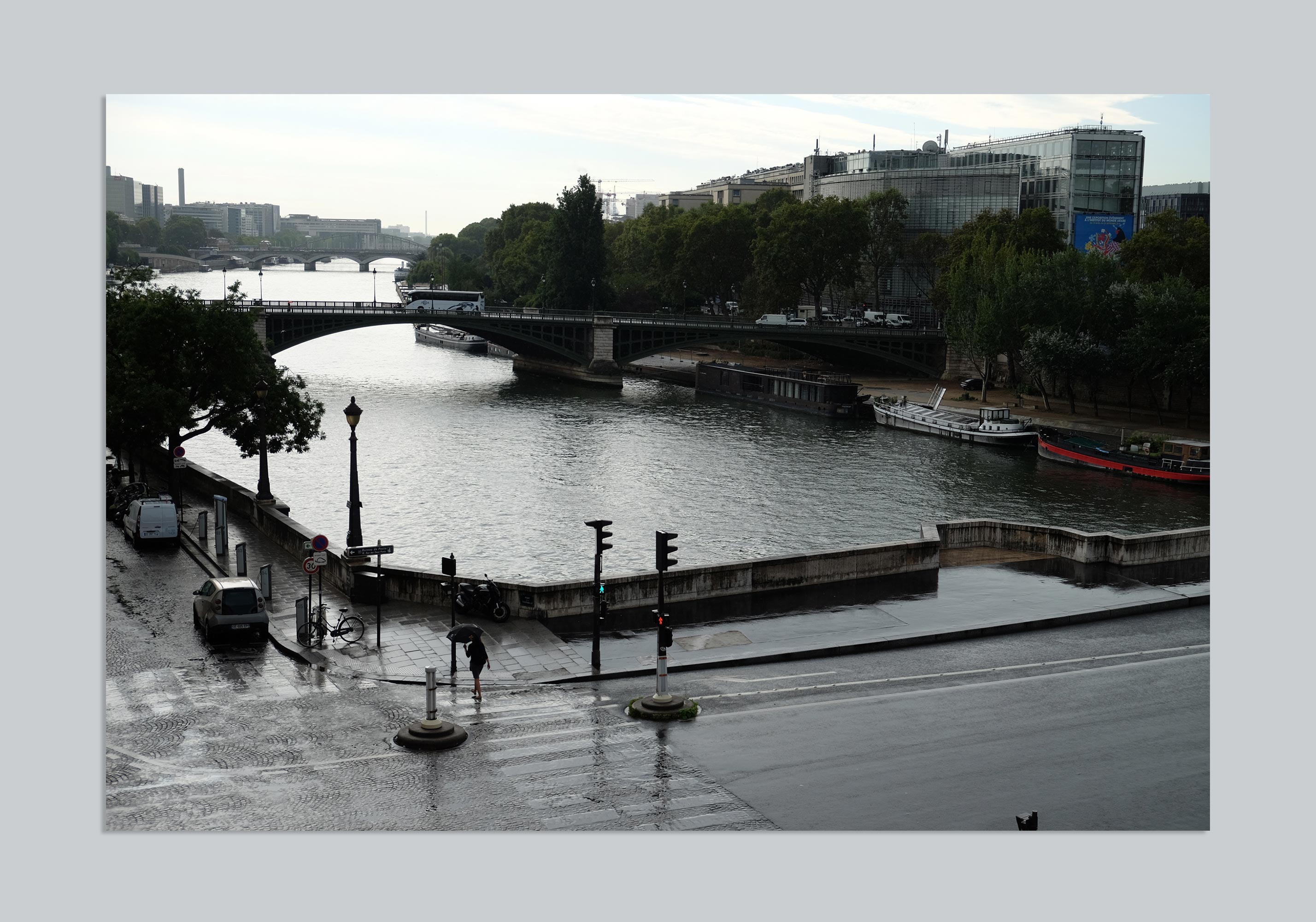

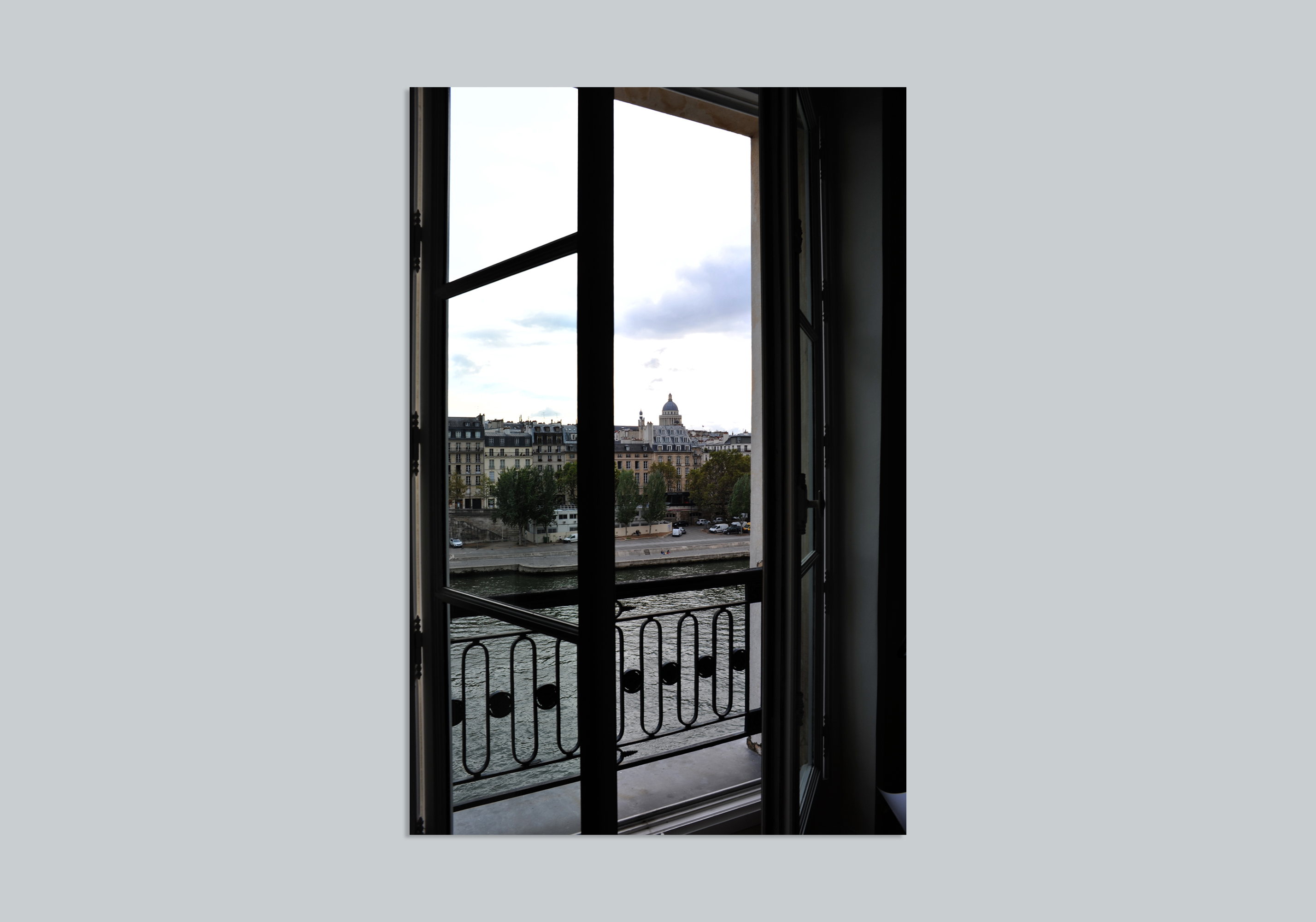

Over six thousand participants of the uprising were forced to flee the Kingdom of Poland after the insurgency’s defeat. Most of the emigrants were men, officers, commanders, and soldiers fighting in the uprising, as they were most vulnerable to post-uprising repressions.

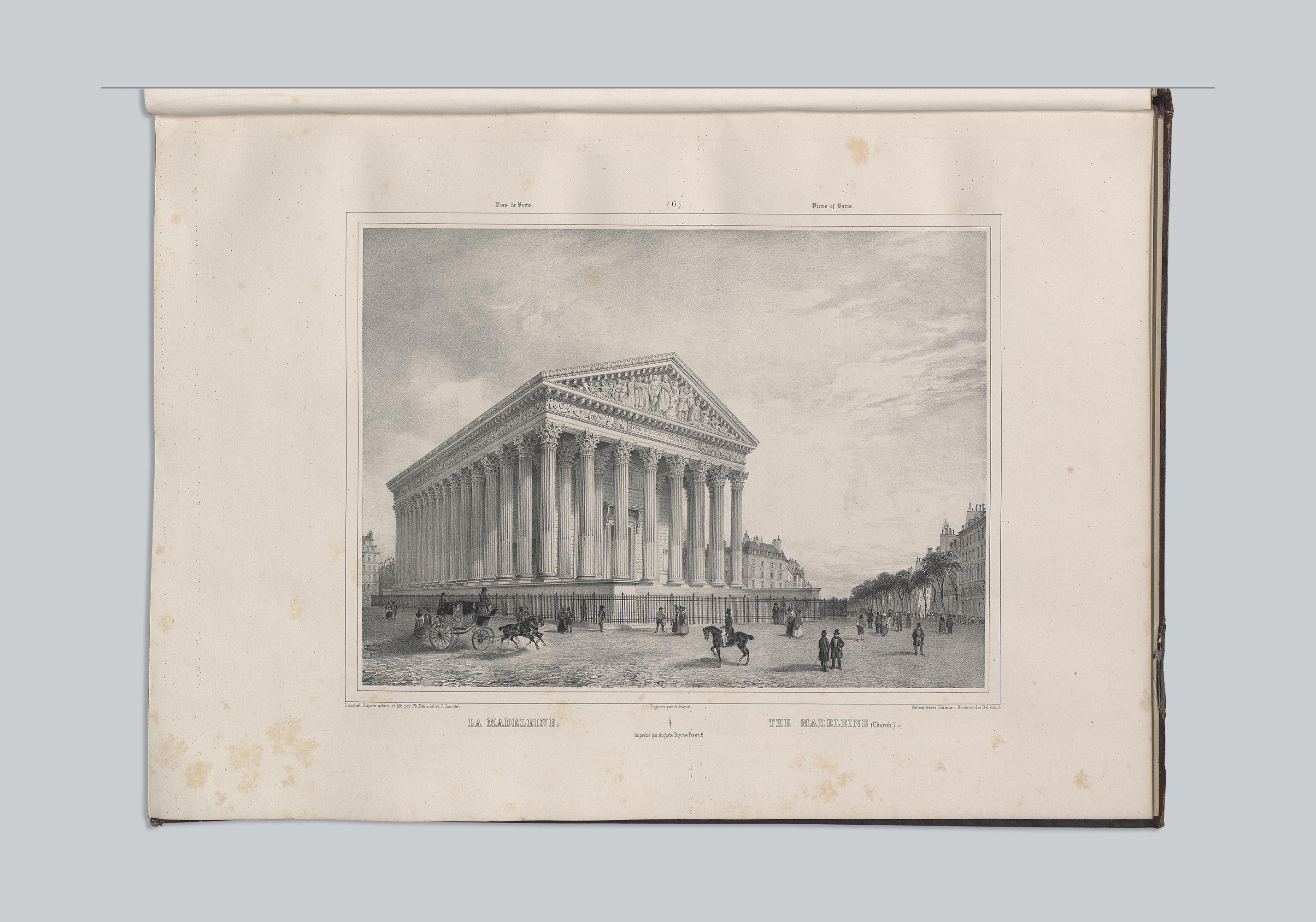

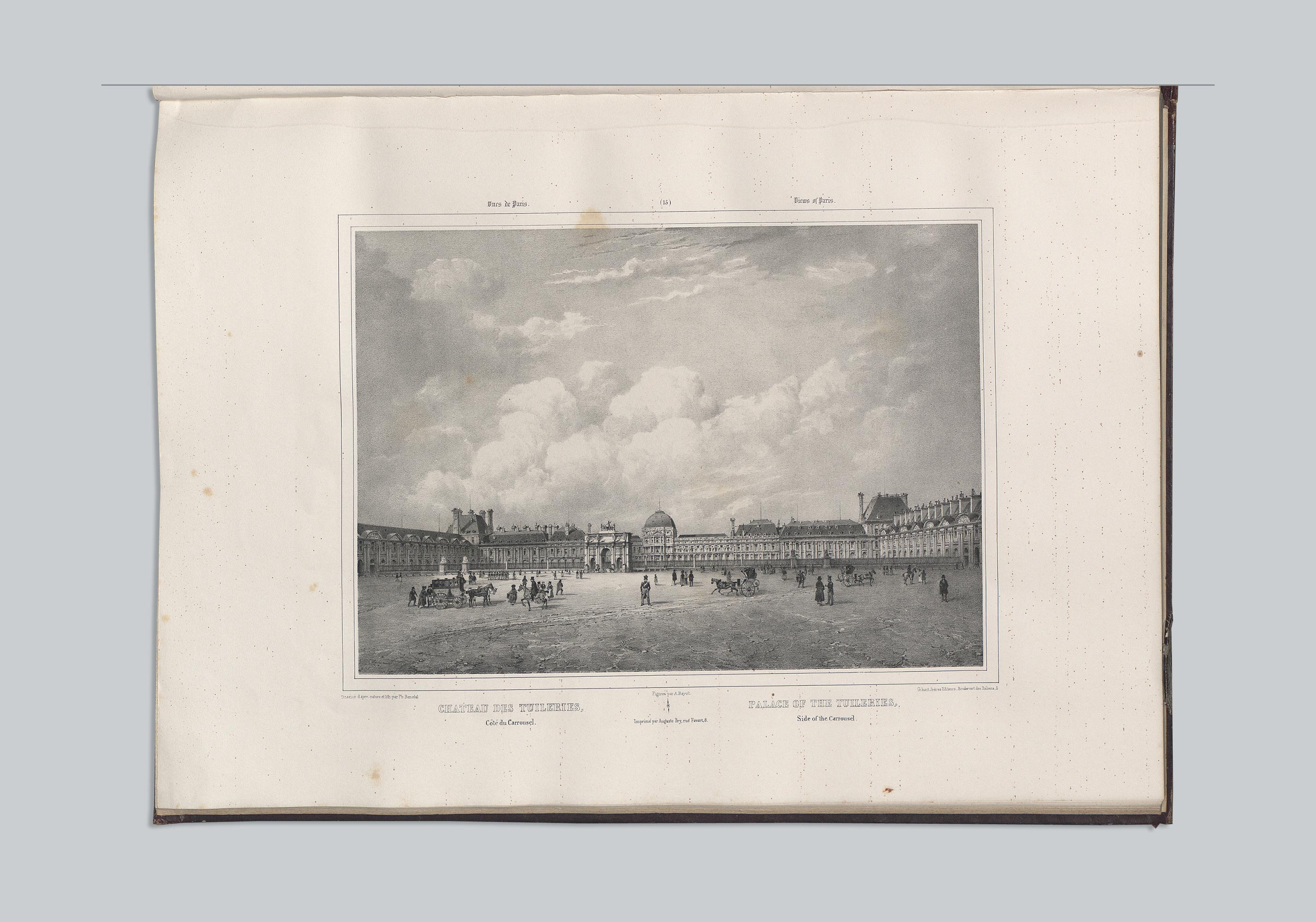

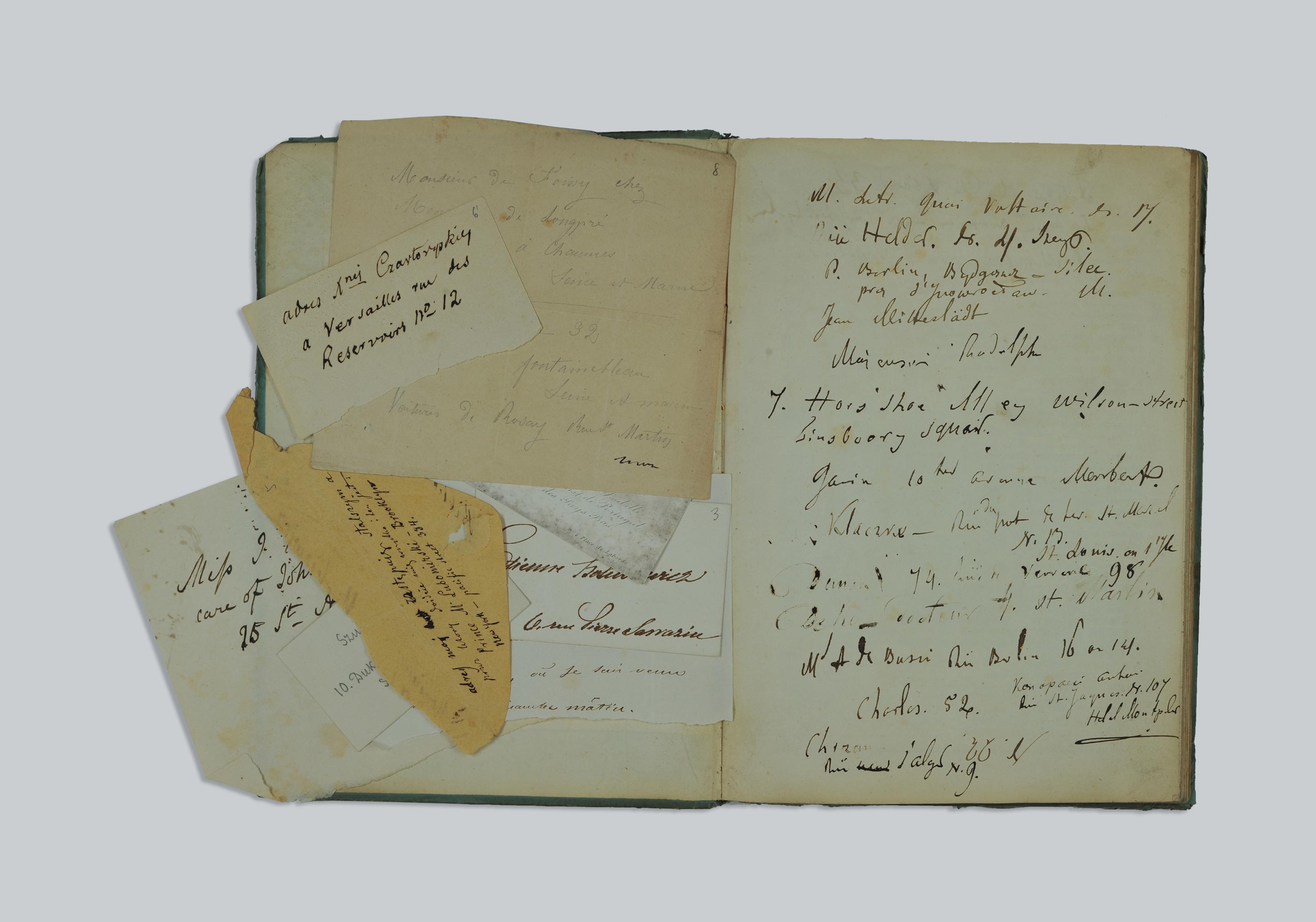

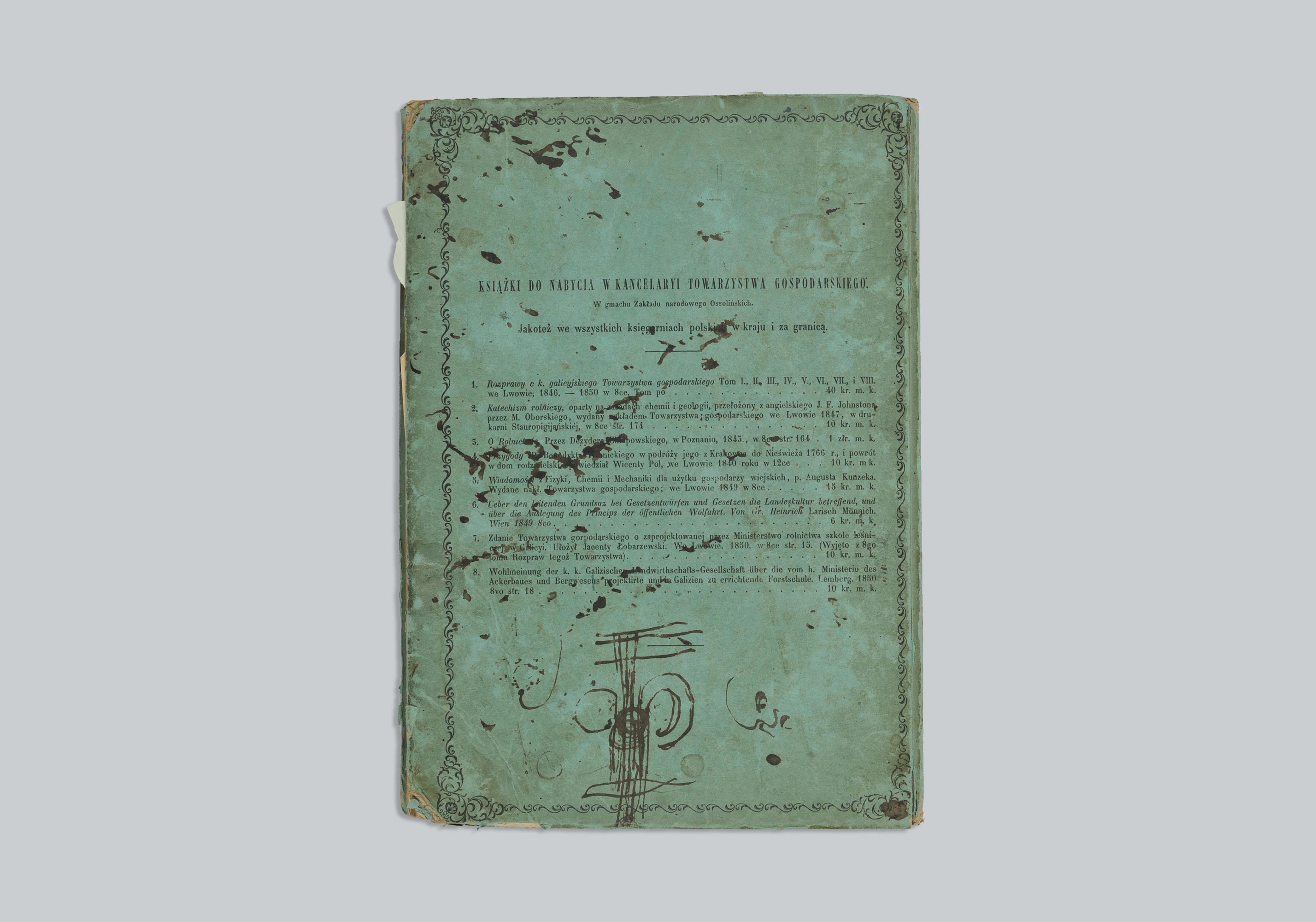

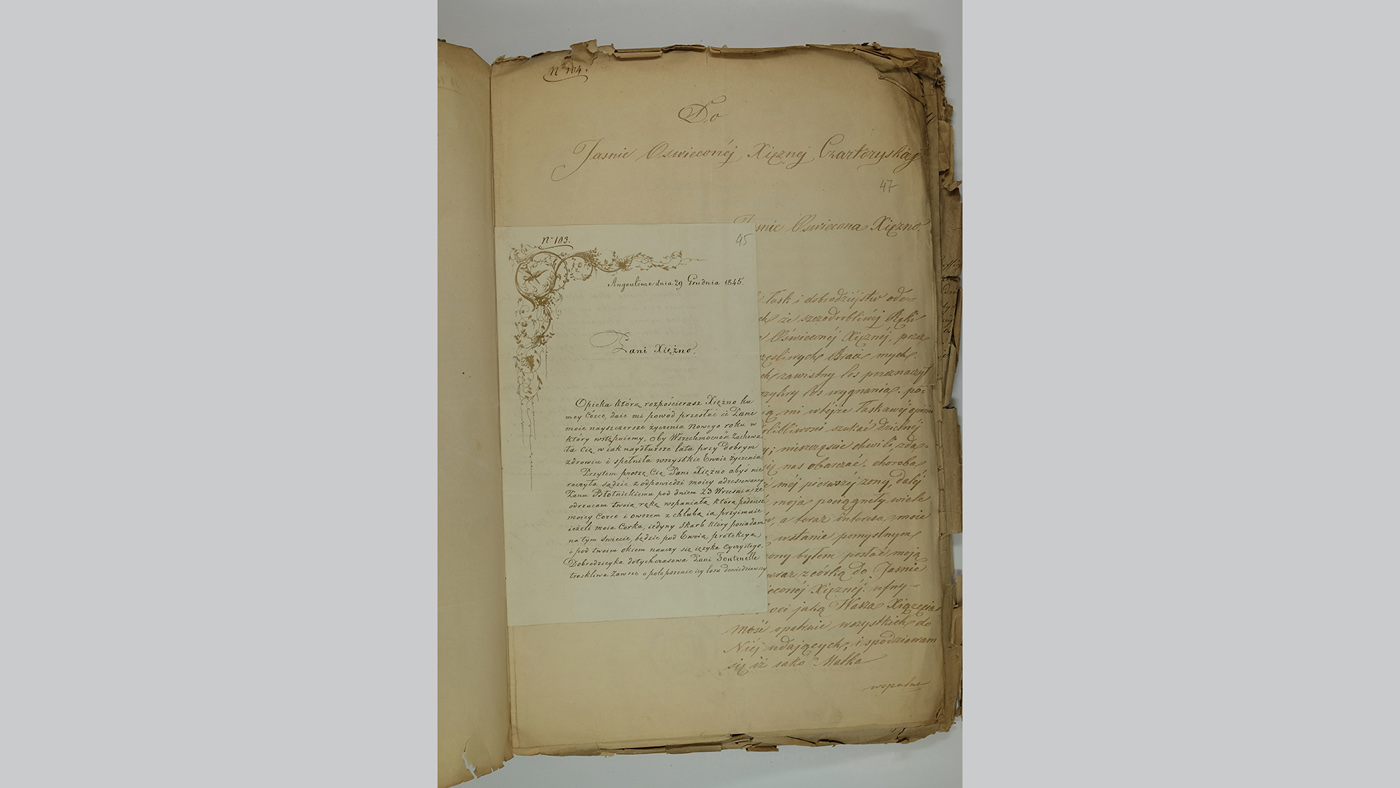

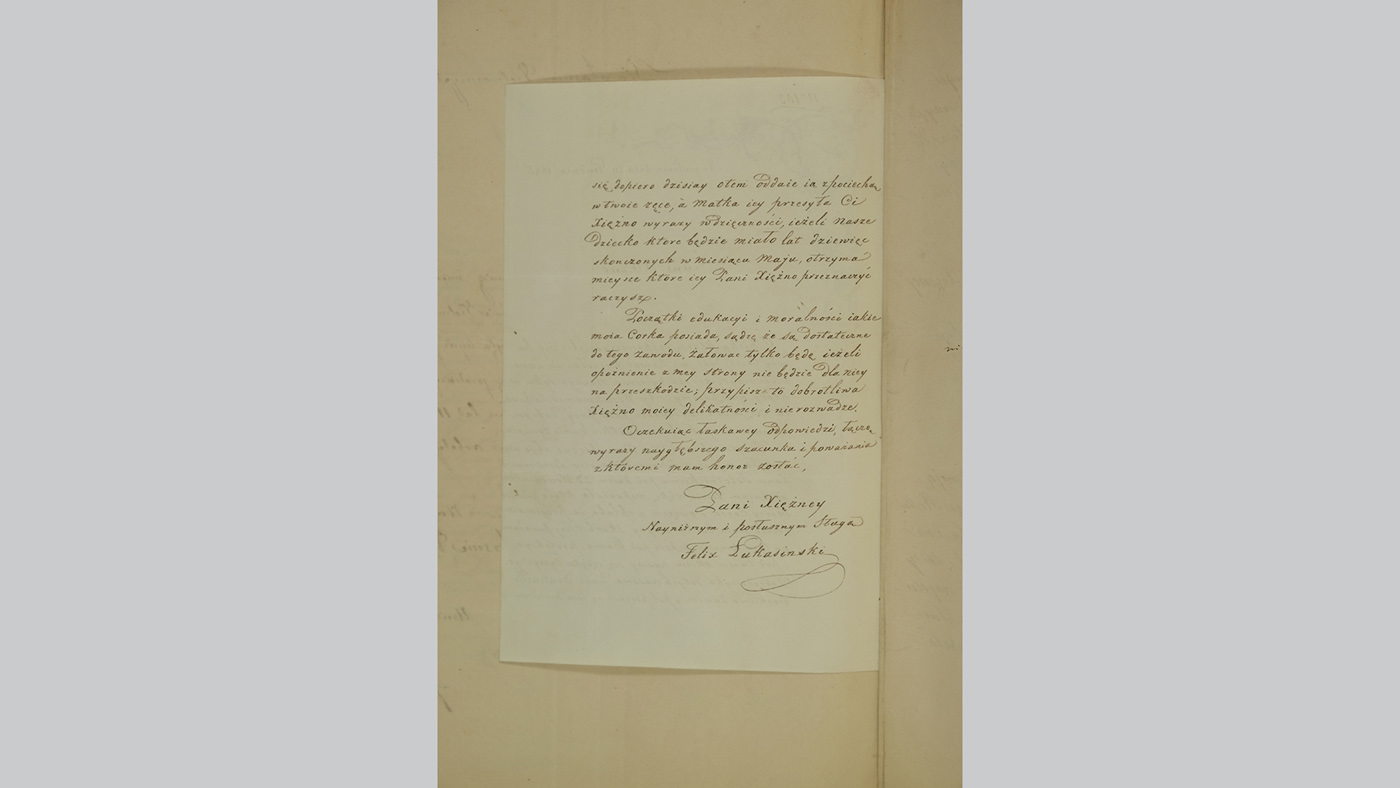

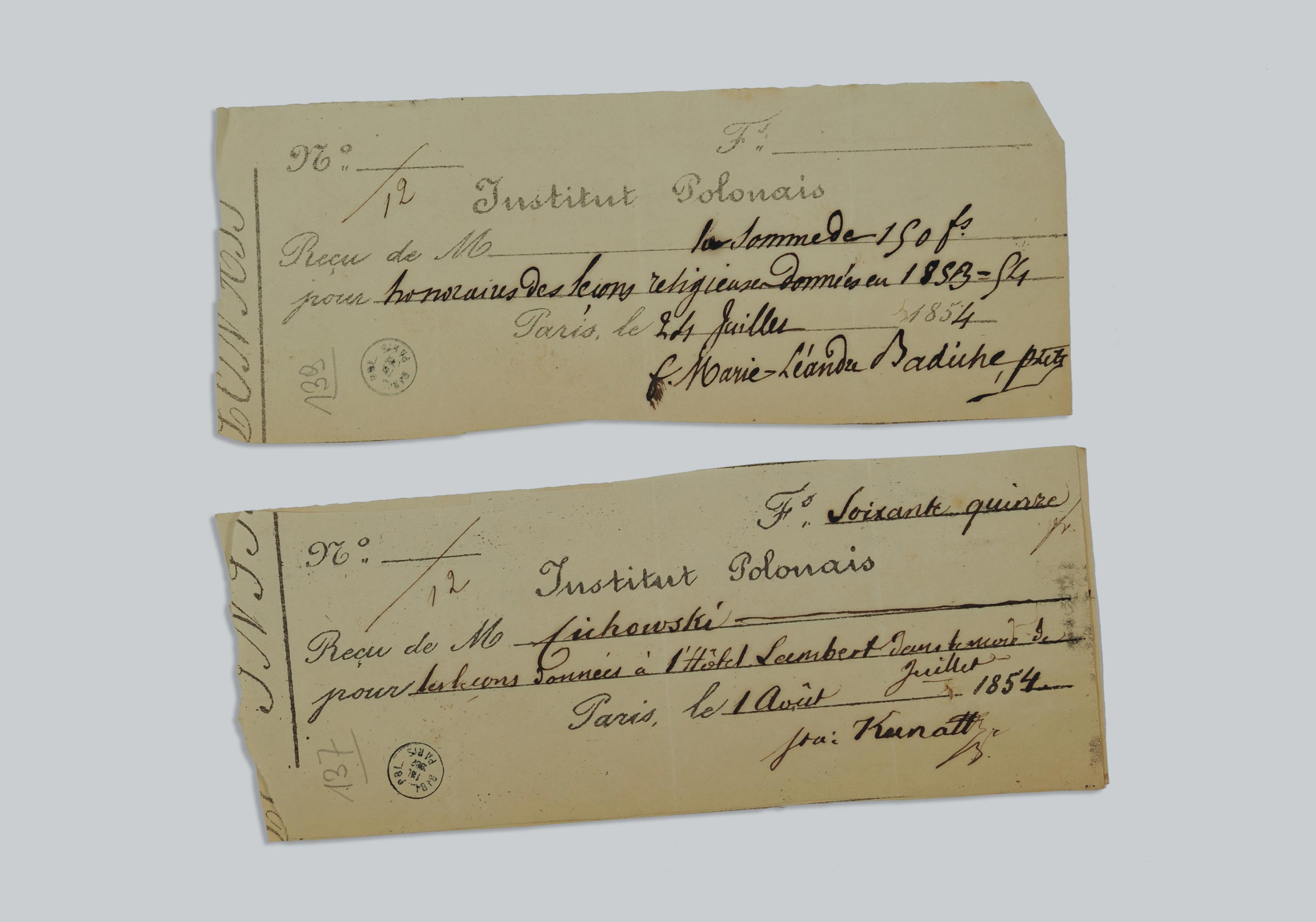

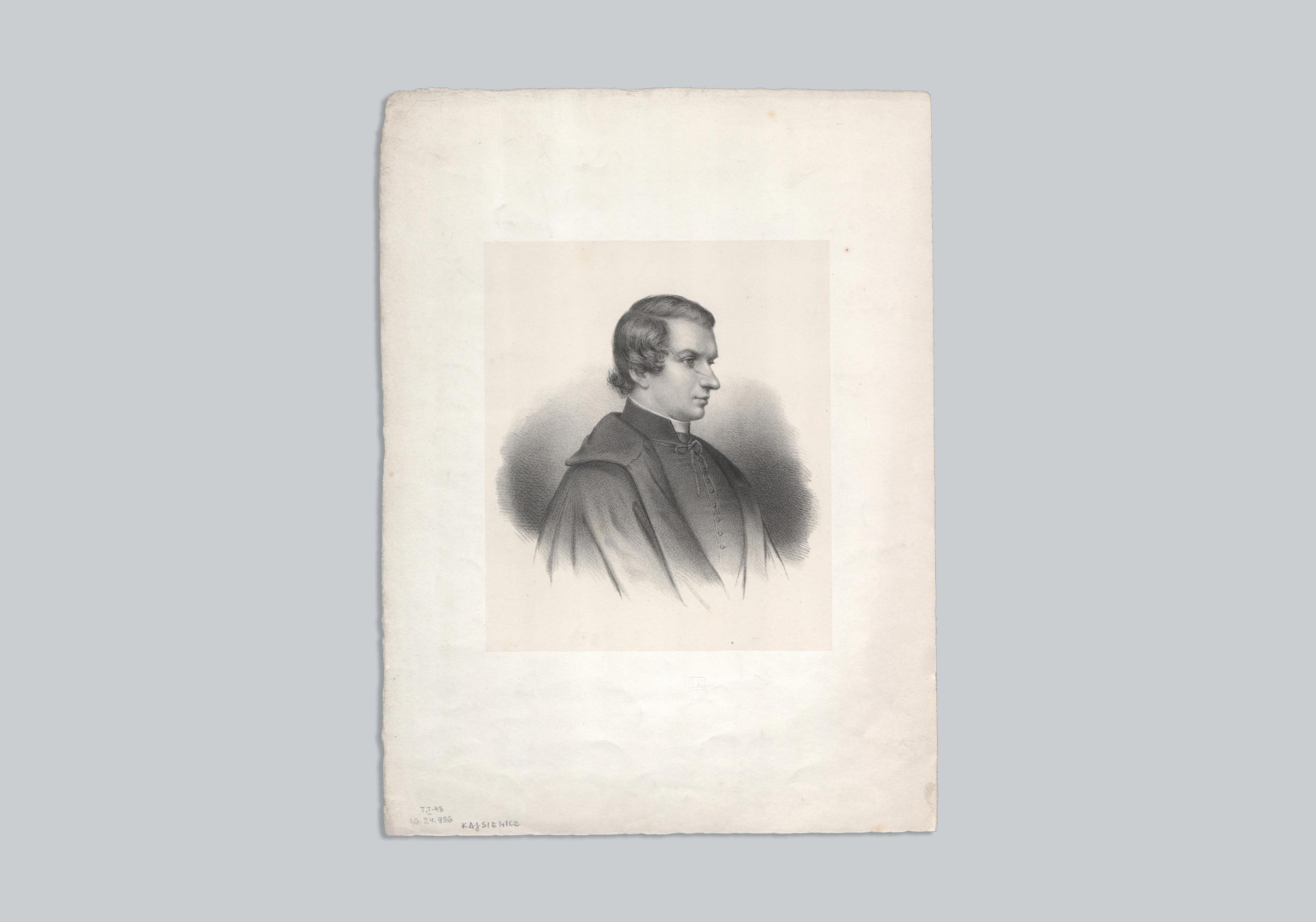

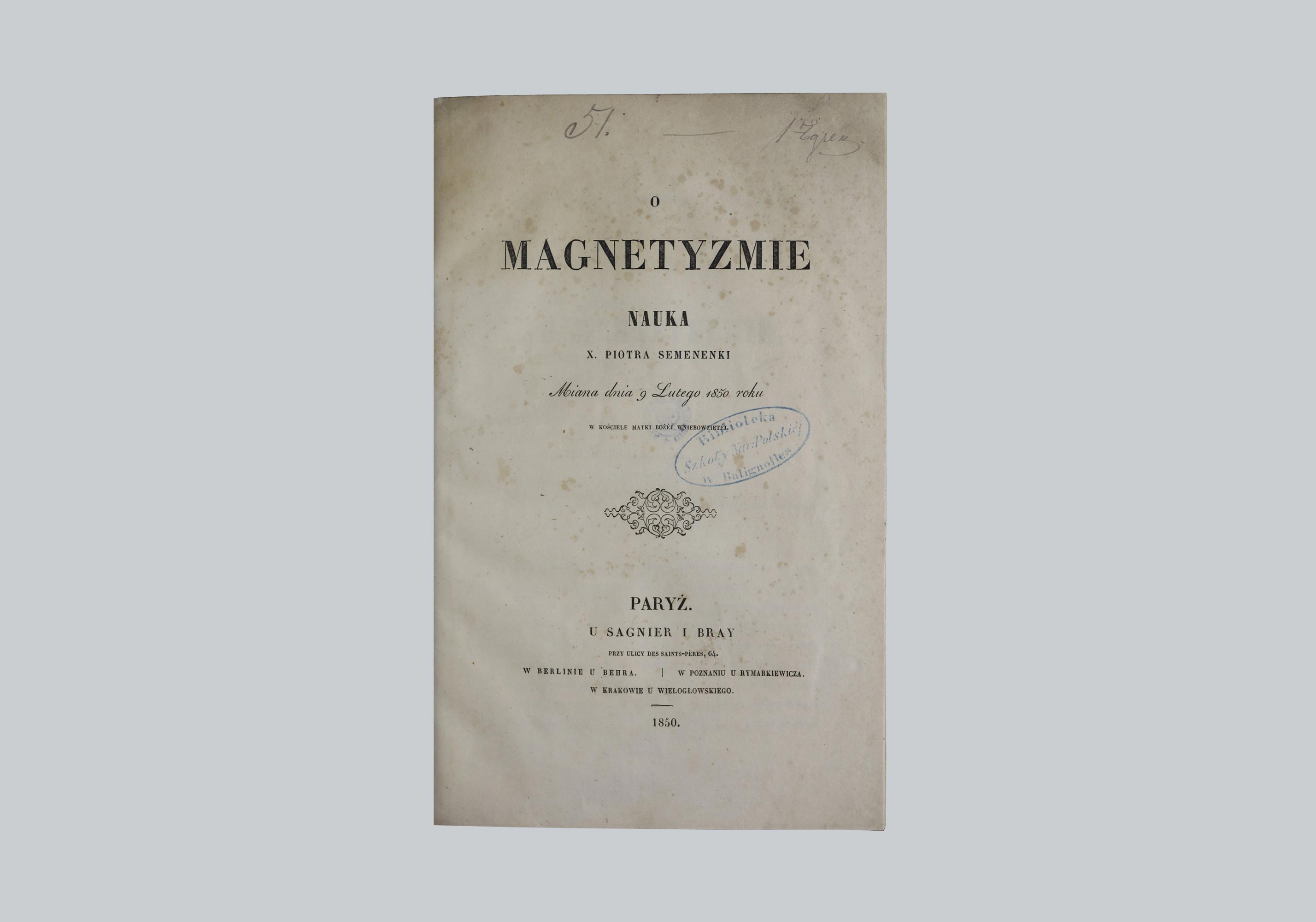

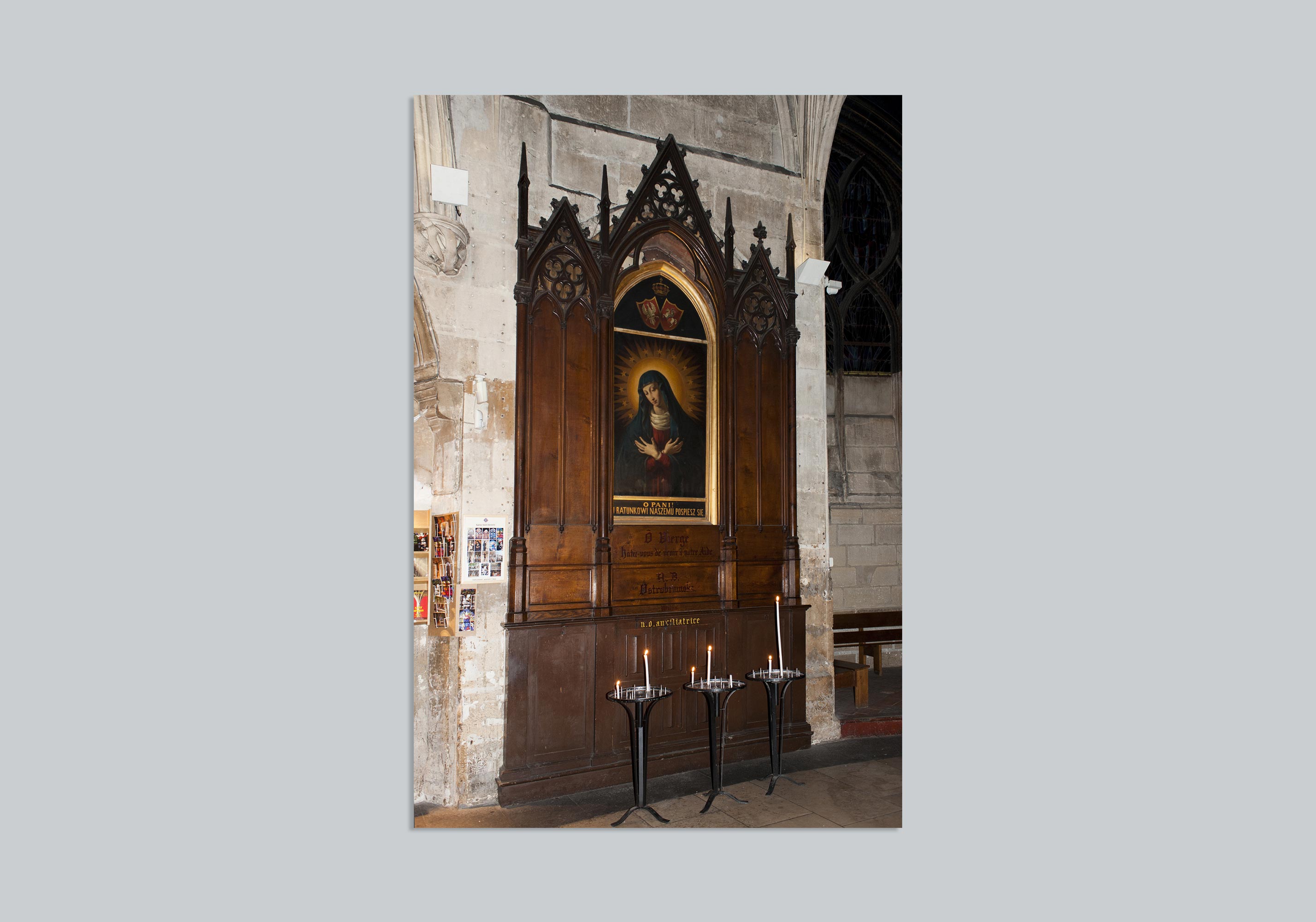

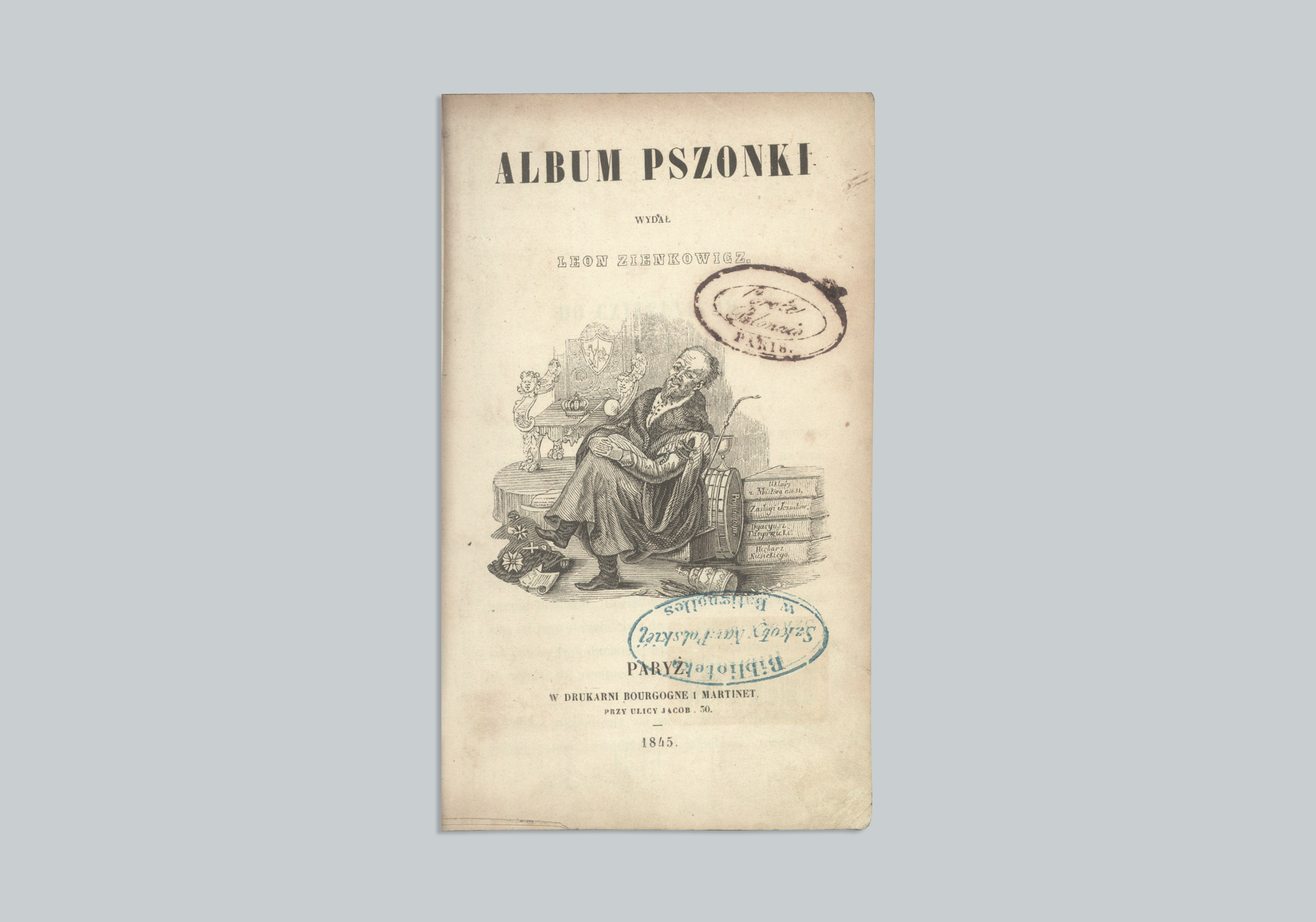

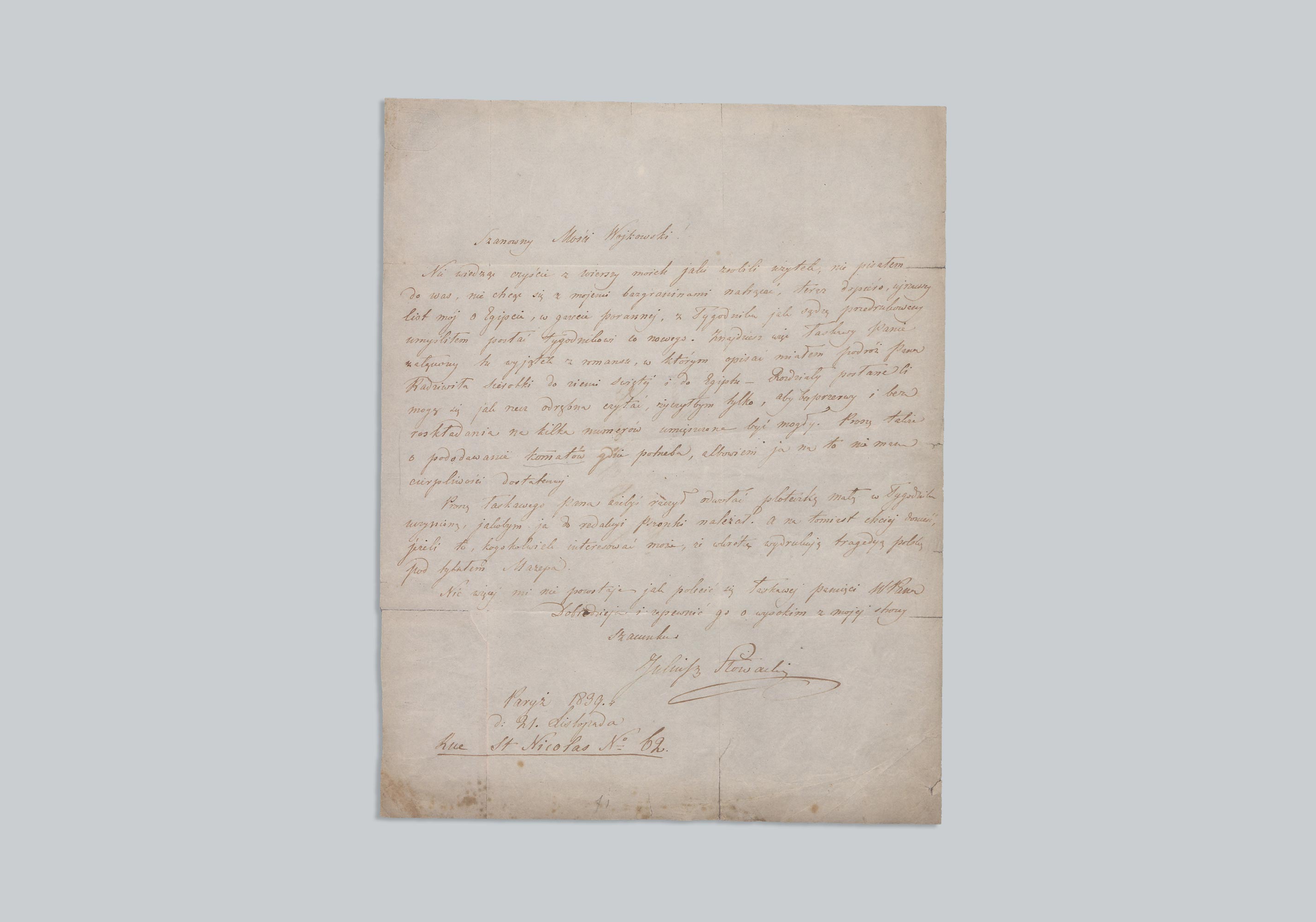

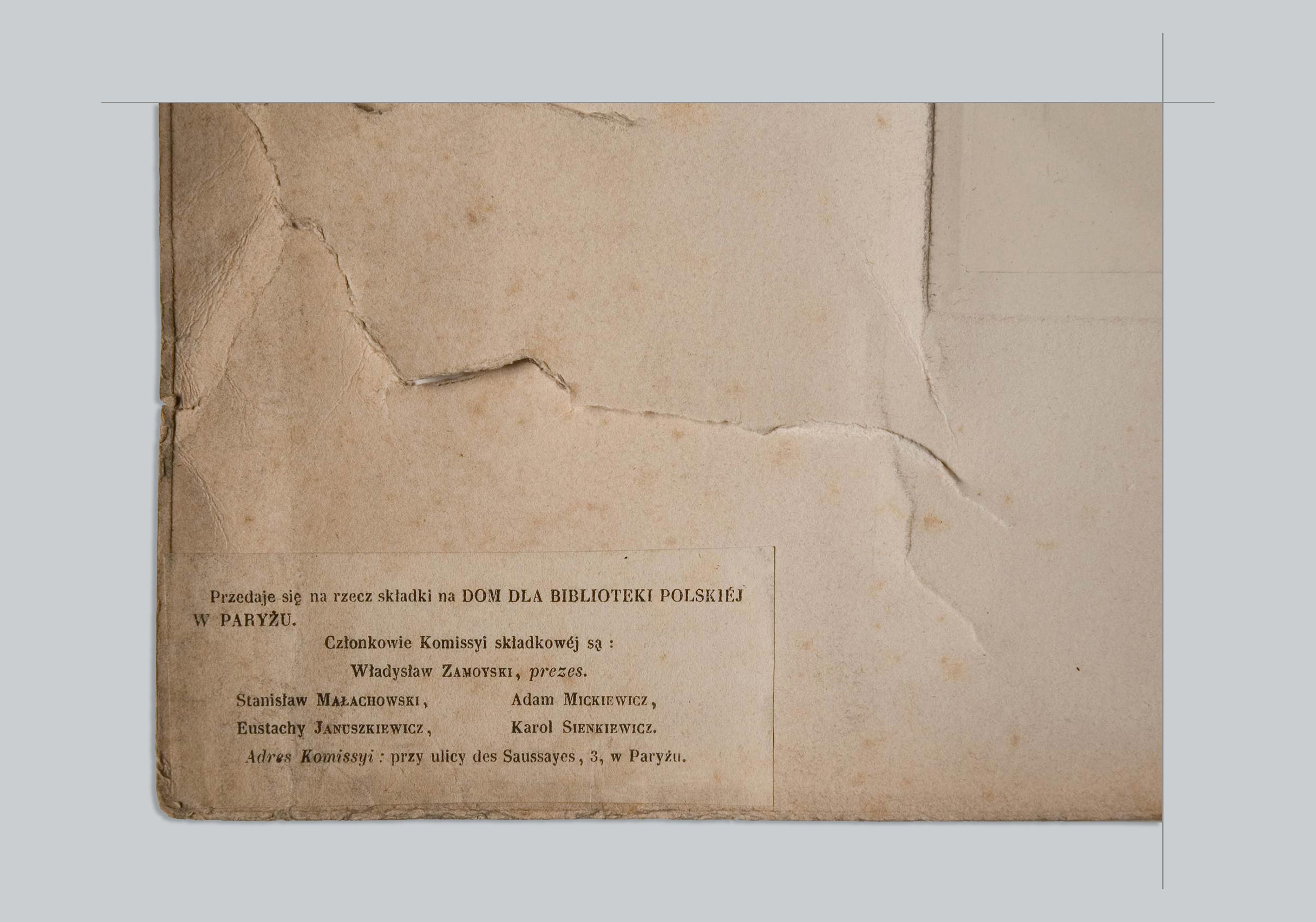

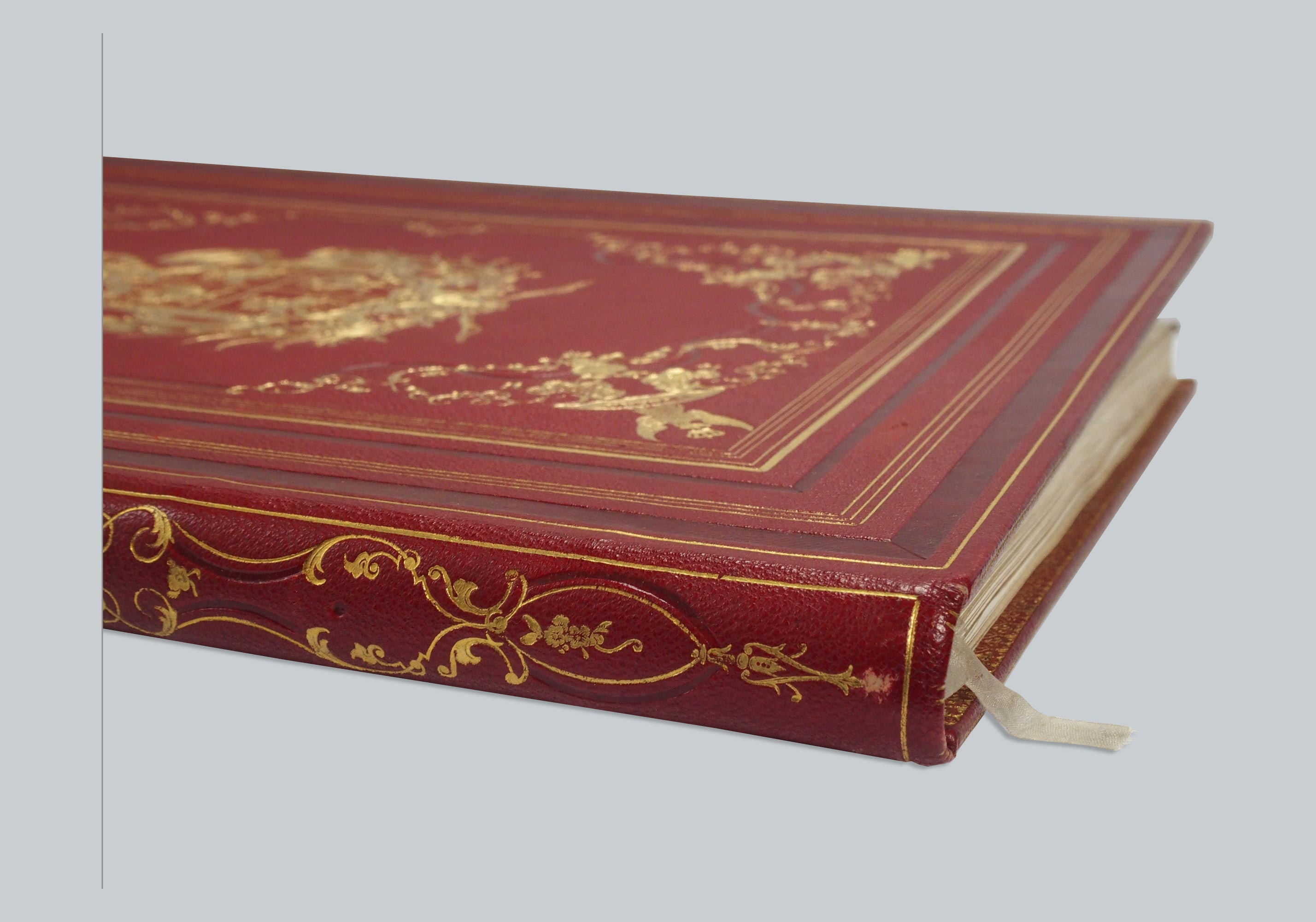

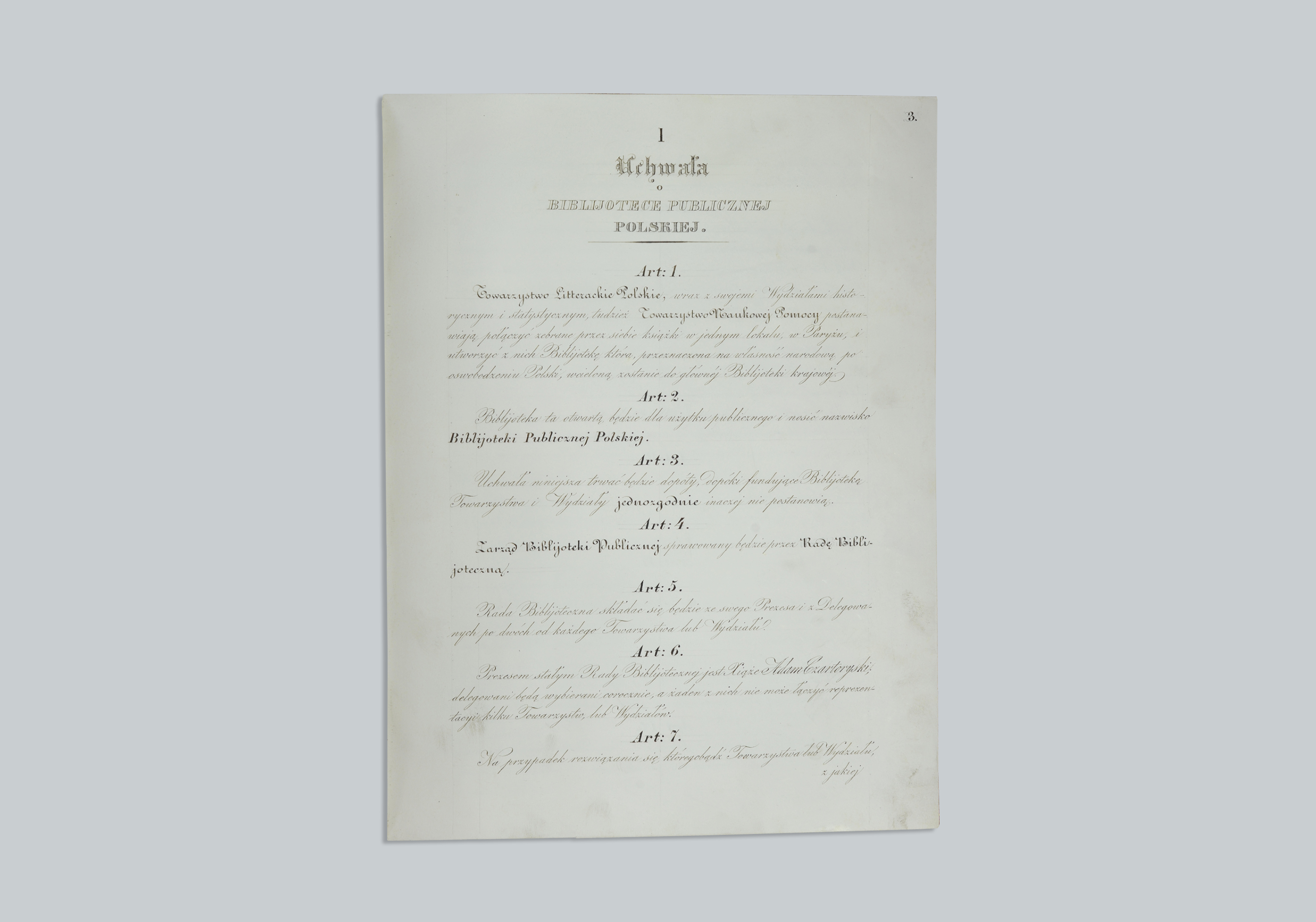

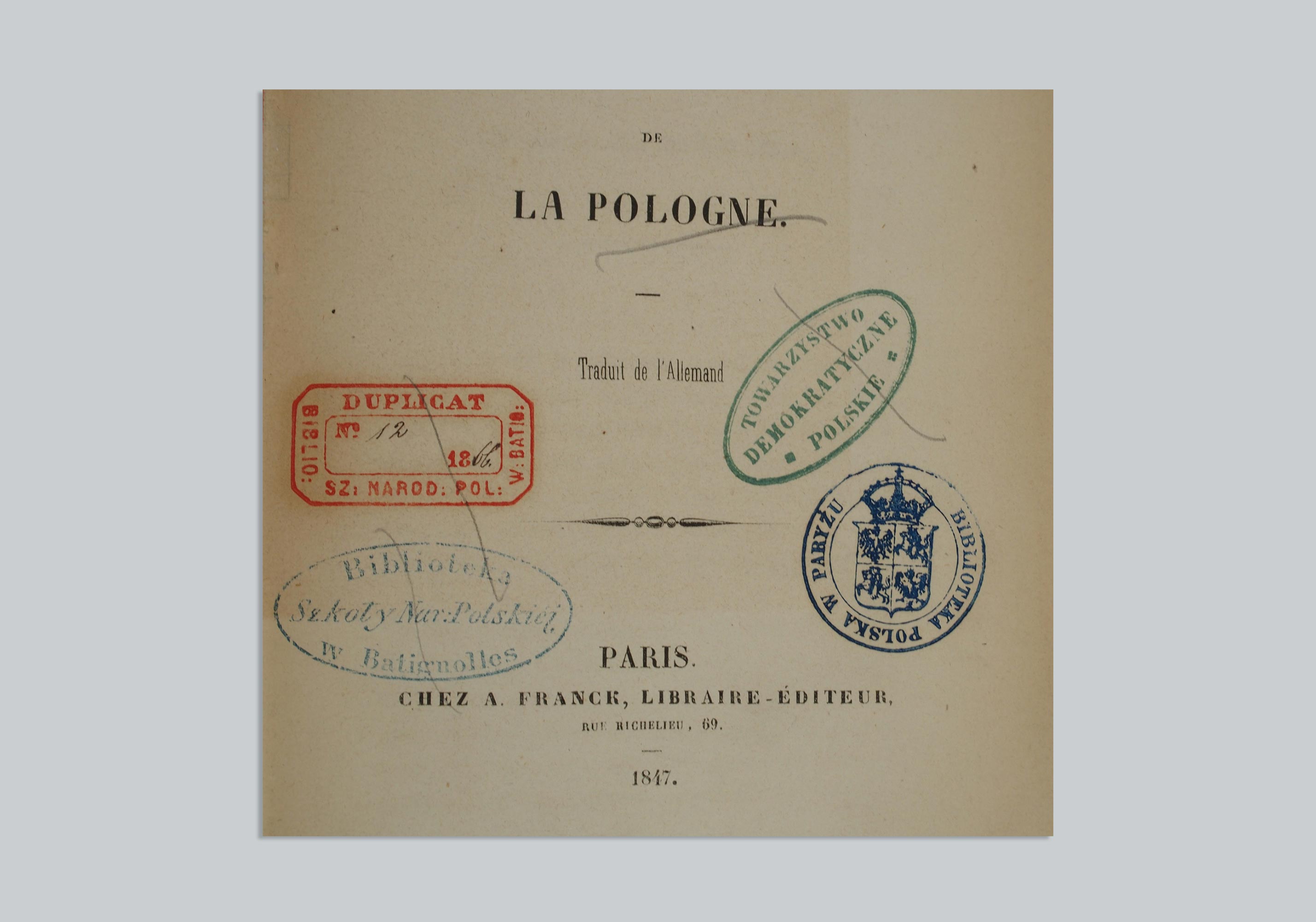

It is not the number of emigrants, however, that constitutes the “greatness” of the movement which today is referred to as the Great Emigration. The greatness of this formation – making foreign lands a common ground for representatives of various groups, civilians and soldiers, laymen and clerics, people injured in the battles and those who never set foot on the battlefield – consists in the joint, though implemented in various ways, effort to bring the idea of independent Poland to life.